archiREEF: The Business Building Coral Reefs

It is no secret that the world’s coral reefs are in big trouble. As well as the mass bleaching events that have become almost routine in an ever-warming sea, they are also being battered by pollution, overfishing and ocean acidification. Given that they support around 30% of all marine species and the livelihoods of over 400 million people–despite covering only 0.5% of the sea floor– the loss of these ecosystems would be catastrophic. Yet that is precisely the scenario we are heading for, as over 50% of the world’s coral reefs have already been lost.

Hong Kong has hardly been a stellar example of reef conservation. According to research by the University of Hong Kong (HKU), the city has (at a conservative estimate) lost 40% of its coral species within the last few decades due to coastal development and water pollution. Yet it is also here that a pioneering new startup is working to undo the damage done to corals, both locally and around the world.

Founded in September 2020 by HKU scientists, archiREEF combines state-of-the-art technology with tried-and-tested techniques to give corals a much needed helping hand in re-establishing themselves. More than that however, it also aims to mainstream ecosystem restoration within the world of business, mobilising urgently needed capital into the protection of our planet.

WELL, here is its story.

The Science Behind archiREEF

Marine biologist and archiREEF CEO and co-founder, Vriko Yu, knows only too well how fast corals can and are disappearing. In 2014, whilst diving in Hoi Ha Wan marine park during a red tide –a massive algal bloom often caused by nutrient pollution– she saw an already unhealthy coral community totally collapse in just two months as the algae blocked out the sunlight it needed to survive. Shocked by what she had witnessed, she became determined to do something about it.

“That was the striking experience that planted the seed [of archiREEF] in my heart” she recalls from a hotel room in Abu Dhabi (more on that later).

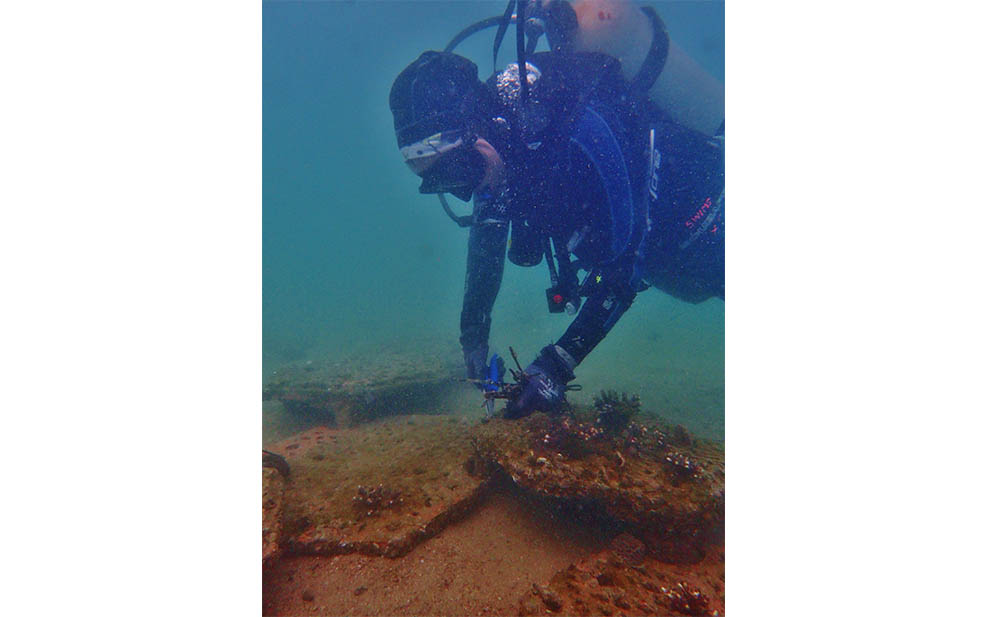

In response to the red tide, the AFCD commissioned HKU to do research on local corals. As part of this work, Vriko and others removed fragments of surviving brain coral from the field and nurtured them in a tank for two years. “What we did was almost like [performing] surgery for coral.” In the controlled laboratory conditions, the coral fragments grew large and healthy. But when they were returned to the wild, most died within two years due to a lack of hard surfaces (substrates) to attach themselves to, like boulders.

“Even in areas where we could find natural substrate, the water conditions –whether in terms of depth or quality– were not the best” says Vriko. “That was the point when we started to think ‘maybe we have to create substrate for them’.” Eventually, Vriko and PhD supervisor, Dr. David Baker, settled on using terracotta tiles, as these had been used successfully in restoration projects elsewhere in the world.

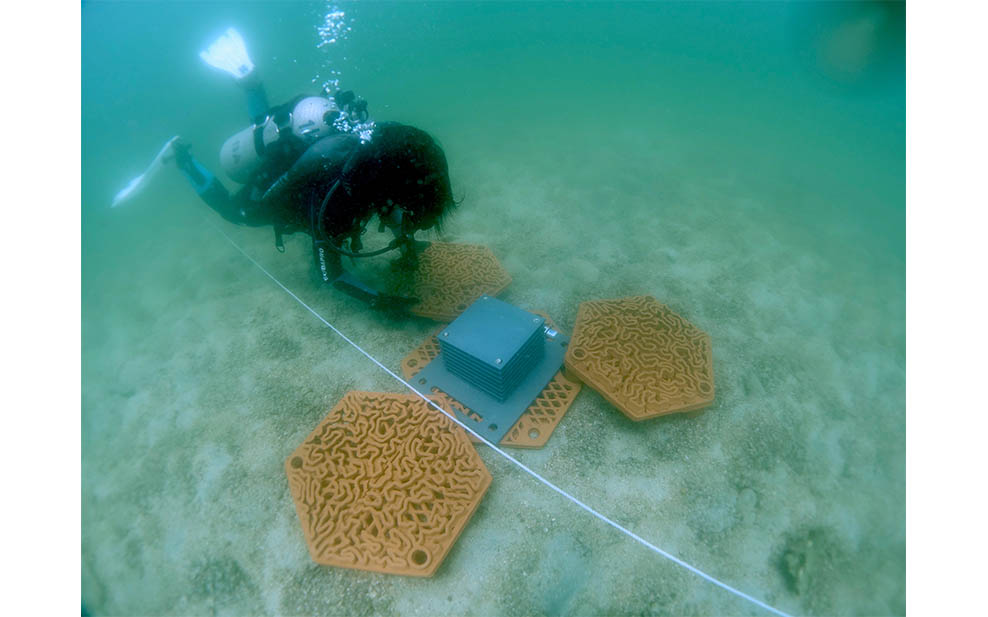

These were not your ordinary, flat, bathroom floor tiles, however. Using a 3D printer at HKU, they created multi-layered, hexagonal tiles with miniature crevices and valleys on them. The reason for this unusual design was that when the tiles were exposed to wave action, it created microturbulence within these little crevices that washed away any sediment that collected in them. This was important as excess sedimentation –caused by changes in currents due to coastal reclamation– is thought to be one reason why natural hard substrate is so rare in Hong Kong (the sediment buries it too deep for coral larvae to access it). These crevices would also provide microhabitats for other marine organisms (including coral larvae) while the hexagonal design would allow for coral fragments to grow and expand more easily.

With approval from the AFCD, Vriko and David deployed their tiles –with coral fragments attached– at three locations within Hoi Ha Wan. In stark contrast to their earlier restoration attempts, 98% of the corals on the tiles survived, four times the number that had done so previously. Several other animals have also made the tiles their home, including a mother cuttlefish who laid her eggs underneath one of them. Clearly, the use of these tiles, if expanded to other areas, could have huge potential for ecosystem restoration.

Getting the money to do this, however, would require Vriko to take a very different path to what her scientific training had prepared her for.

From Science Project to Startup

In academia, projects typically receive grants and funding based on how innovative they are or how much impact they will make as a published research paper. Frustratingly for Vriko, her coral restoration work did not really satisfy either criterion in the eyes of the Hong Kong academic community. Seeking an alternative source of money, she decided to use her work as the basis for a business, both to generate funds for expansion and as a means to spread awareness of coral restoration. So, in September 2020, she and David co-founded archiREEF together.

“[We] just needed a channel to bring this technology to a larger audience and a startup was one of the solutions” she says.

For someone with a scientific background however, making the shift to entrepreneurship was no easy feat and at first, Vriko struggled to adjust to operating in a business setting. In particular, communicating her knowledge in a way that was understandable for the public and especially investors was a very steep learning curve. Starting a company at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic also didn’t help matters.

Luckily, thanks to funding from the Hong Kong Science and Technology Park (HKSTP), archiREEF was able to get through these difficult early days. In 2021, the company entered into the HKSTP’s Elevator Pitch Competition (EPiC), a global pitching event which gave it the chance to sell itself to investors. In one of the most challenging stages of her entrepreneurial journey so far, Vriko had just three minutes to give a pitch covering archiREEF’s background, business model and attractiveness to investors.

“For me, to be able to deliver what I’ve been doing for the last 8 years [in 3 minutes] was really tricky” she recalls. “It takes a lot of practice and a lot of failure to come up with a script that can capture people’s attention and that they can understand.”

For all of her nervousness however, her pitch not only managed to beat 600 other applicants to the final round of EPiC, but then went on to beat 9 other finalists to win the competition. Suddenly, thanks to the media attention around EPiC, a startup that wasn’t even a year old yet had the attention of big money and the offers came flooding in.

“After that, we got [about] 20 investor calls” says Vriko. “It was an important milestone for us.”

Business Model

If you’re familiar with ‘adopt an animal’ campaigns –in which people pay to sponsor the conservation of a given wild animal species– then you already have some idea of archiREEF’s business model.

archiREEF operates on a subscription, starting with wealthy clients paying a fee to restore a certain area of coral reef in their name. Once the tiles are laid down, the client is then required to sign up for a subscription package for at least three years to pay for the maintenance of the new reef. In return, archiREEF will offer services to the client and/or their company, like running workshops or giving talks on coral for their staff.

Thus, archiREEF’s business model not only channels corporate money into coral reef restoration, but also provides a means to educate people who otherwise might never learn anything about it.

So, how’s it going?

It’s still too early to determine how much impact archiREEF is likely to have in terms of coral reef restoration. However, at the time of writing, it has been selling its subscription package to corporate clients for six months. Meanwhile, an even more encouraging sign has recently come from outside of Hong Kong.

Thanks to the considerable media coverage of Vriko and David’s work –both before and after EPiC– word of it reached the ears of sustainable investors in the UAE, which is a leader in coral reef preservation and restoration in the Middle East. Intrigued by the possibilities of archiREEF’s technology, they invited Vriko to come to Abu Dhabi to trial it in local waters, with generous financial support from a sovereign wealth fund. In light of this, archiREEF is now setting up a new production facility there.

“We see great potential [in the UAE]” Vriko remarks. “It’s not just that the clients are ready to be part of the solution, but also that the overall support in investing in green technology is quite mature here.”

By the end of this year, archiREEF aims to have deployed tiles at two more sites in Hong Kong (including the coral hotspot of Bluff Island) and at one site in Abu Dhabi. Later on, they hope to expand to restoring other important marine ecosystems like oyster beds and mangroves, which are also rapidly disappearing.

Of course, the question surrounding any coral restoration effort is this: How do you prevent your work being derailed when, under current scenarios, climate change is projected to kill 90% of all corals by the end of this century. The answer to that question, according to Vriko, is that you can’t. At least, not on your own.

“If we continue business-as-usual, I don’t think any of the restoration work is going to effectively mitigate the impacts of climate change” she says. “For our solutions to be able to succeed, we need collective effort from everyone to cut down carbon emissions.”

Ultimately, coral restoration itself can only ever be part of the solution. To really give coral reefs a chance will require comprehensive, multi-pronged action, including raising awareness outside of the scientific community of both the crisis and its solutions, hence the integral role of education in archiREEF’s business model.

“It’s not just about investors. It’s more about general support” says Vriko on the future success of her company. “If more people talk about [ecosystem restoration], our clients will know that it’s important and that will be a stronger incentive for them to adopt [our] solutions.”

Bringing this awareness to a wider audience will also require more scientists and conservationists to step outside of their comfort zones. At present, most science graduates tend to shun the world of business for careers in sectors that are more aligned with their training like NGOs, education or environmental consultancy. But given how much the corporate world currently contributes to the destruction of the natural one, perhaps it is long overdue for more startups helmed by people with the knowledge of how to reverse this. To those feeling apprehensive about doing this, here is Vriko’s advice:

“I think it is scary for sure […] but from my experience, it has been very rewarding” she says. “I think that this is the best time for [scientists] to make a difference in a different space and ask for public buy-in. So, if you have any ideas that you think need to be heard, just try it.”

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Thomas Gomersall

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social for daily news, competitions, and more.