Online Animal Abuse: How to Spot it and Stop it

Imagine you’re surfing the internet and you come across a video of an animal doing something that seems amusing. Maybe it’s a dog walking on its hind legs, or a slow loris being tickled, or a monkey wearing clothes and showing its teeth in an ostensible grin. Seems cute, even funny, doesn’t it?

But for the animals, it is anything but.

Unbeknownst to many, behind the scenes of most videos like these lies a much darker side of psychological torment, maternal deprivation and even serious physical abuse, both intentional and unintentional. While a large percentage of online animal abuse is obvious, a considerable portion of it is not, making it all the easier for unsuspecting internet users to click, like, share and comment on it, increasing their popularity and rewarding content creators for their abuse. All while social media companies largely turn a blind eye.

WELL, in this article, we reveal the horrifying extent of animal abuse on the internet, how to recognise it when you see it, and what you and social media companies can do to stop it.

The Cruel Reality

We may not typically think of animal abuse as an online thing, but in fact it is shockingly common on the internet. Between July 2020 and August 2021, the Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition (SMACC) documented 5480 animal abuse videos on TikTok, YouTube and Facebook, which cumulatively got over 5 billion views.

“We’re talking about billions of views here. There’s shares included in that, engagement; so the figures are really, really high” says Nicola O’Brien, lead co-ordinator for SMACC.

Sadly, one reason for the prevalence of these videos is that they are profitable. According to the SMACC member organisation, Lady Freethinker, over just 3 months in 2020, YouTube earned an estimated $12 million dollars in ad revenue from animal abuse videos, while the content creators themselves earned $15 million. This in turn may explain why social media companies seldom reinforce their own (often vaguely worded) policies against animal abuse, even in spite of regular reporting of it.

“There’s one video where someone takes a large stone and throws it on a kitten, squashing and killing it. This video has been up for 10 years!” O’Brien laments. “We have reported it many times, as we know other people have, and it is still there.”

In addition, content creators have ways of avoiding accountability. They often possess accounts with multiple platforms so that even if content is removed from one, their followers can still access it on another. They are also protected by a lack of personal information sharing between social media companies and authorities, as well as the inherent difficulties of identifying abusers from videos alone.

Cruelty Disguised as Cuteness

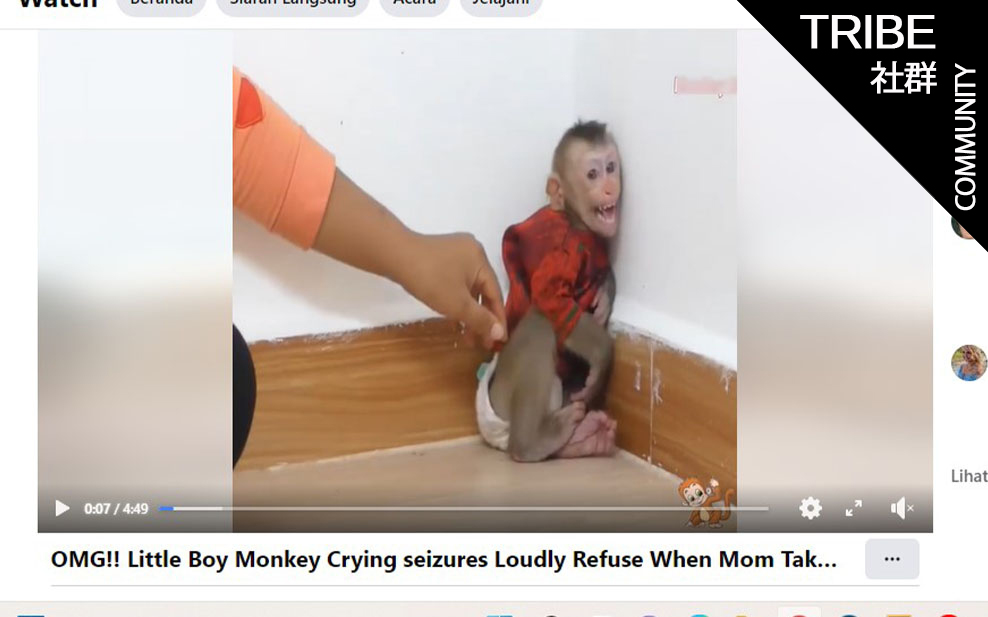

Perhaps the biggest obstacle in tackling online animal abuse is that some of it can seem quite benign to the casual viewer, who may not recognise signs of distress in the animals involved. For instance, in some primates like macaques, grinning–which many would interpret as a sign of happiness– is actually a fear response. It is also common to see animals behaving in ways that, while not overtly abusive at first glance, are very unnatural for them, which should raise questions of what is happening to create this illusion.

“A big thing we find with monkeys [is] they are walking on their hind legs as humans do. […] That is not how those animals move and often they are trained in quite cruel ways to get them to stand up in that manner” says O’Brien. “[But] someone watching that won’t see that training and that cruelty that’s happened beforehand to produce that video, and it might just appear that the monkey’s walking around and it’s completely normal and fine.”

Another increasingly common form of online animal abuse is fake rescue videos, which depict animals being saved by humans from dangerous and distressing situations, like traps or the coils of pythons. But in fact, the animals have been deliberately put in harm’s way to make the content creator look good for ‘rescuing’ them.

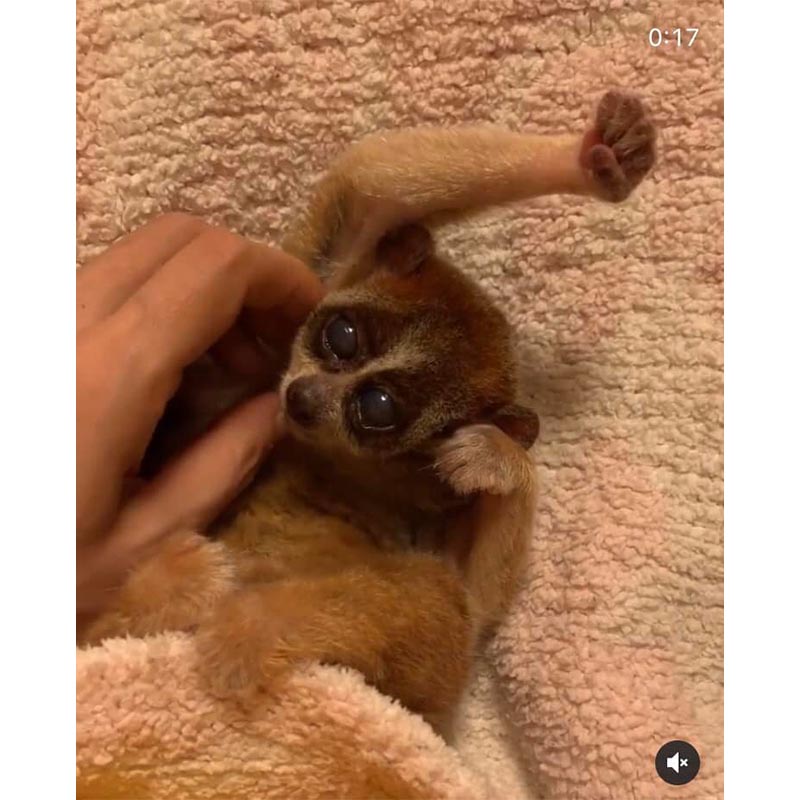

Even when intentional abuse isn’t involved, well-meaning content creators (and by extension, the viewers who enable them) can still end up abusing animals through simply not understanding their needs and behaviours. Slow lorises for instance are naturally nocturnal, have large territories and a specialised diet of tree sap, and when threatened will raise their arms as part of a defense gesture. But in most online videos of them, they are kept in small, brightly lit rooms, fed on inappropriate, unhealthy foods like fruit and rice balls, and are tickled by owners who misinterpret their arm raising as a sign of playfulness instead of fear.

“Maybe there isn’t [physical] injury being done to the animal. But the animal is still suffering psychologically” says O’Brien. “It’s not necessarily something that a general member of the public would be able to see and evaluate.”

Cancelling Online Animal Abuse

The responsibility for tackling this problem lies largely with social media companies, who can start by adopting clearly worded, standardised definitions for animal abuse within their policies to ensure its prohibition on their platforms. “We are actually in discussion with [a major social media platform], trying to get them to update their policy so that it widens what is classed as animal cruelty. At the moment, it’s very brief, very general” O’Brien reports.

They can also place warnings on potential abuse content to prevent it from getting engagement –as Instagram has recently started doing with content related to the illegal wildlife trade– train their moderators to better recognise animal distress signals, and prevent content creators from moving abuse content to other platforms. There are also artificial intelligence systems that can be used to detect and remove abuse content more efficiently.

“It’s not feasible to rely on the public or on animal welfare organisations to have to find and report this content” O’Brien remarks. “[Platforms] need to be proactively removing it.”

That said, there are things that the average internet user can do about online animal abuse too, the most important of which is not to engage with it in any way. If you aren’t sure if a video constitutes cruelty or not, look at the title, description and still images before clicking on it, as these usually give you a good idea of the content.

Another good tactic is to check the content creator’s account to see if they have posted other similar videos to the suspected abuse content, as this would imply that they are primarily keeping animals to exploit them and may not have their best interests at heart. This tactic is particularly useful for spotting fake rescue videos, as it is unlikely that anyone would come across animals in danger frequently enough to make repeated videos of them without manufacturing those dangerous situations.

If you do find cruelty content, be sure to report it to either the platform itself or to SMAAC. “We know that [platforms] do look at their percentages of reports and what themes they are receiving. So we want to feed into that and teach the algorithm that this type of content is not good” says O’Brien. If you do report to SMACC, your report will be logged into their databank, allowing them to further analyse patterns of online cruelty and pressure social media platforms to have it removed.

Finally, it pays to know what some of the less obvious forms of animal abuse in online content are:

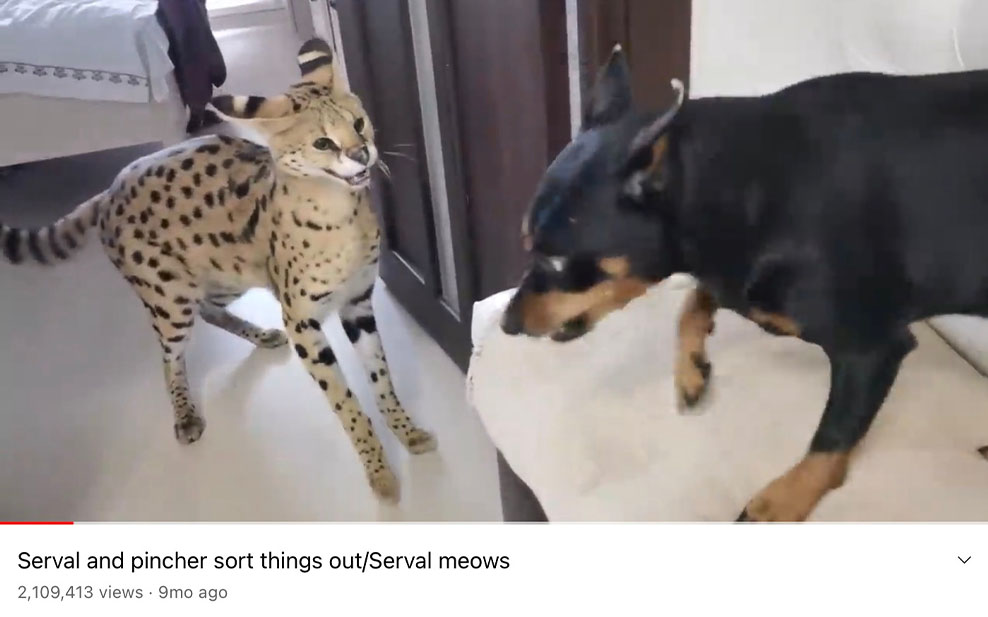

- Wild Species as Pets: As many wild species, like otters and slow lorises, have highly specific needs that are very difficult to meet in a home environment, keeping them as pets is inherently abusive. While some may claim that the animals in the video were bred as pets, due to the difficulty of breeding many wild pets in captivity, it is more likely that they were trafficked from the wild instead. If in doubt, do some research on the species in question to decide how likely it is that its needs are being met in captivity.

- Humanising Animals: Any instance of animals being made to behave like humans should raise questions of abuse. Behaviours like wearing clothes, walking on their hind legs and eating human junk food are so unlike their natural behaviours that they are likely being forced to do them under threat of physical punishment. Even if that isn’t the case, this humanisation can still be uncomfortable, undignified and unhealthy for them.

- Animals as Entertainers: Similar to humanisation (which itself is often part of animal performances), performing tricks for entertainment is often done against the animals’ will and with the threat of punishment. When not performing, they are often deprived of the social interactions and physical space they need. In addition, many wild animals used as entertainers are kidnapped from the wild and separated from their mothers at a young age when they are easier to train.

- Psychological Torture: This abuse can take many forms, from withholding food to spraying animals with water to scaring them with a prop, mask or other animal. While this can seem like light-hearted teasing to us, for the animals it can actually be deeply distressing, particularly for ones who depend on humans for their physical and emotional needs.

Before you go:

To report a suspected case of online animal abuse, visit the SMACC’s Report a Concern page.

For further tips on how to recognise online animal abuse, watch SMAAC’s series of videos on the subject: Ask Yourself.

To learn more about online animal abuse and what can be done to stop it, check out SMACC’s 2021 report, Making Money from Misery.

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Thomas Gomersall

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social media for daily news, competitions, and more.