Astrid Andersson: Queen of the Cockatoos

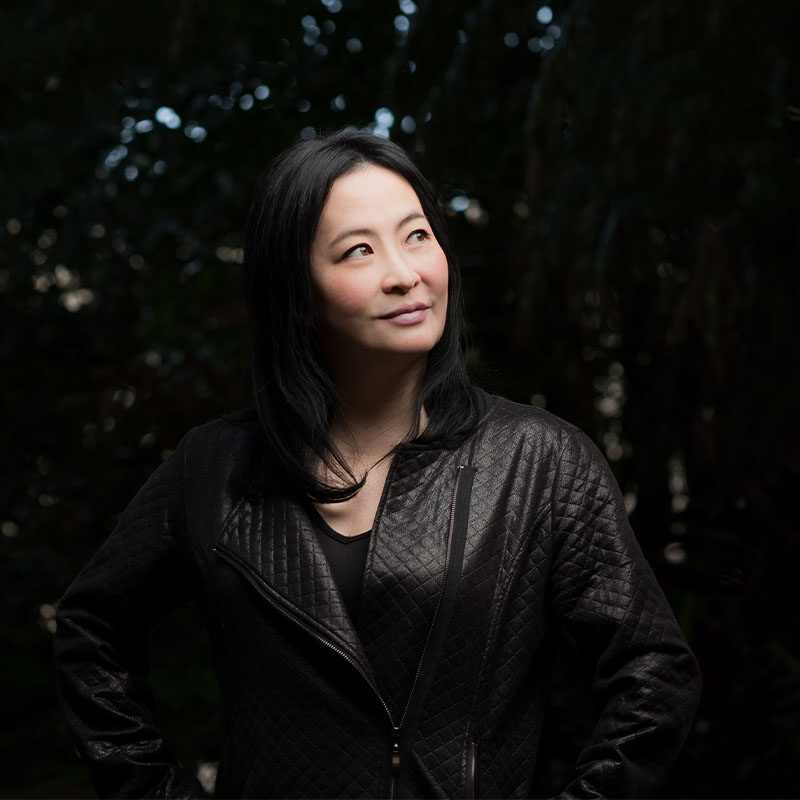

It’s early evening and in Hong Kong Park in Central, most of the visitors are slowly making their way towards the exits to go home. But high up in the park’s observation tower, Astrid Andersson has only just arrived. Indeed, this brief period of twilight is exactly the right time for her to be here. Alongside a couple of assistants from the University of Hong Kong (HKU), she patiently surveys the sky and treetops around her with her binoculars, waiting for a very special animal to fly in for the night. Then there’s a raucous screeching and she spots it: a large white parrot with a lemony head crest. Excitedly, she and her assistants whip out clipboards and record this observation, the first of many this evening, to be sure.

The parrot in question is a yellow-crested cockatoo, a bird that is as much a part of the urban landscape of Hong Kong Island as the Star Ferry Terminus or the IFC tower. Yet ironically, it is actually native to Indonesia and East Timor. According to urban legend, the local population is descended from pet birds released by the governor of Hong Kong just before the Japanese invasion during World War II. But while that war may be long over, the trade in yellow-crested cockatoos has continued to this day, driving wild populations to levels so low that the species is now classified as ‘critically endangered’ by the IUCN, just one step away from extinction.

When trying to save any species or population, a certain level of understanding of its ecology and the threats facing it is needed for an effective conservation plan. Yet despite their familiarity to the locals and dire global status, virtually nothing was known about the yellow-crested cockatoos of Hong Kong.

That is, until Astrid chose to take up a PhD at HKU to research them. Five years later, she has produced one of the very first comprehensive studies of the ecology of the cockatoos in Hong Kong and developed a forensic tool to help monitor the local pet trade. Both of these achievements could massively aid the conservation of both this population and the species as a whole. What makes them all the more impressive is that she had no prior academic background in scientific research. In fact, her initial career path looked quite different to what she is doing today.

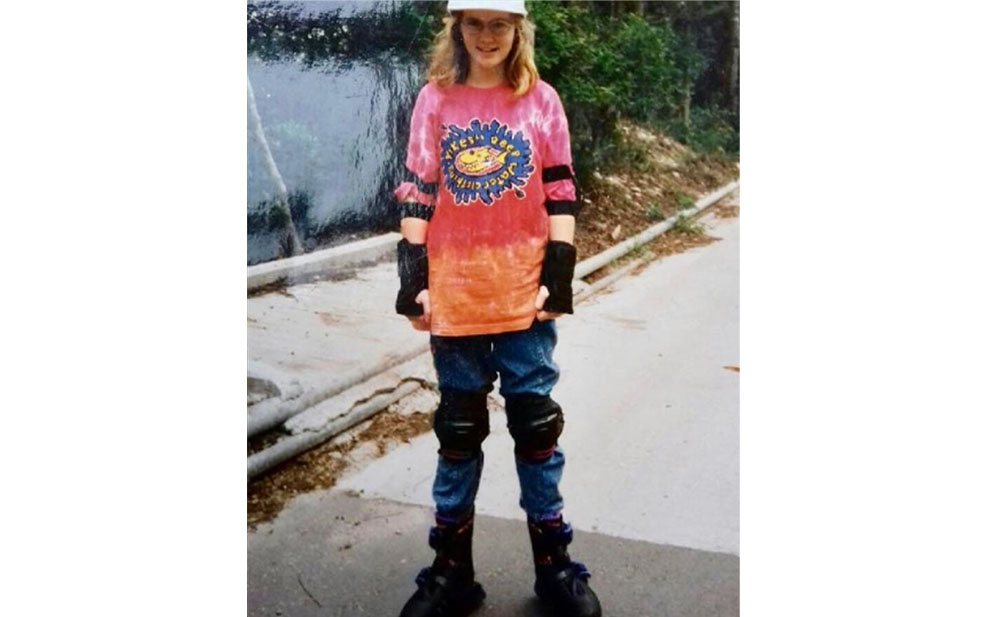

Consistent throughout her life, however, has been an intense love of wildlife and the environment. And it is this passion, evident from a very young age, that has driven her to success in conservation.

In this WELL, WHO? Feature, we share Astrid’s inspiring story. Her journey shows all those aspiring to make the difficult break into a career in conservation that, with enough passion, commitment and a willingness to learn, they too can make their own meaningful, even ground-breaking, discoveries to help make our planet a better place for wildlife and humans.

Fledgling Years

Astrid was born to Swedish parents, but moved with them to Hong Kong when she was two and considers the city to be her real home. With the beaches and greenery of southern Hong Kong Island right on her doorstep, Astrid grew up with a healthy appreciation of nature and the outdoors and spent as much of her time as possible engaging with it. On weekends and after school, she could often be found roller-blading through the country parks, searching under rocks for snakes or swimming in the sea looking (mostly in vain) for sharks. Meanwhile, holidays were spent roaming the forests and lakes of her native Sweden. Unsurprisingly, with this love of the environment came an attendant, life-long, almost all-consuming love of animals.

“Most children enjoy animals, but I was obsessed; constantly drawing, searching for or reading about them” Astrid reminisces. “I remember when my dad asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I replied: “I want to work with animals because they’re the best and also…if you work with animals, you don’t have to do maths!” (Ironically, as a scientist, she has to deal with maths and statistics a lot for data analysis).

But beautiful scenery and rich biodiversity weren’t the only things about Hong Kong that forged Astrid’s interest in conservation. So too did the city’s strong ties to the illegal wildlife trade, signs of which were very evident in her day-to-day life. For example, as a young child, she and her mother would sometimes walk past one of the many ivory shops in Hollywood Road. The sight of the dismembered elephant tusks prompted an inquisitiveness that would serve her well in her later career. “I asked a hundred questions like ‘What is that?’, ‘How do people get that?’, ‘Does it hurt the elephant?’” she recalls. “When I got a little bit older, I had the same questions about the shark fins that I saw.”

Seemingly, someone with these sorts of interests should naturally go into a career in ecology or conservation. But for Astrid, it was not clear what exactly what she should do to get started in the field and her career advisors at high school were unfortunately not able to provide much assistance. “I didn’t really have the career guidance that would have been helpful” she laments. “No one explained to me how I could work with animals in terms of research and conservation. That wasn’t really made clear.” So, she ultimately chose to study Politics and International Development at the University of Leeds in the UK. However, she does not regret this choice. On the contrary, she recommends it to others with similar interests to her. “It’s about how you can ensure that when a country or a region is developing, there’s a balance struck between economic development, social considerations and the environment” she says of her course’s relevance to conservation.

From Words to Birds

After graduation, Astrid moved to Thailand to work as a journalist for The Phuket Gazette, a biweekly tabloid paper for expats living in the famed holiday destination, which itself provided plenty of juicy material for stories. “It was a very interesting time when I got my journalism chops. A lot of crazy stuff happens on that island” she recalls. Later, she worked as a freelancer for (mostly) Asian publications like TIME Magazine Asia, National Geographic China and The Business Traveller Asia Pacific.

But Astrid’s passion for wildlife and conservation never waivered and she was determined to work it into her career in some way. Thus, as a journalist, she mostly covered environmental issues as her speciality. During the four years that she lived in Thailand for, she also kept her connection to nature alive through exploring its pristine jungles and coral reefs.

Sadly, tragedy struck when her father was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer. His untimely death made her recognise the fragile, finite nature of life and the importance of spending whatever time we have doing what we love. “It was this experience that really pushed me to start dedicating all my energy, effort and time to conservation.” Thus, Astrid started volunteering for environmental NGOs, which eventually turned into paid part-time or project based positions at Greenpeace East Asia, WildAid and Humane Society International.

Her NGO career was defined by the Hong Kong wildlife trade, which she wrote reports and did extensive research on. One of the highlights was a 2015 project for the Humane Society, surveying and raising awareness of pangolin consumption. This work gave her a wealth of valuable experiences in lobbying, awareness raising, applying for funding and various types of fieldwork, which would put her in good stead for what was to come later. “I really grew my network, knowledge and skills set at that time – learning everything from how to covertly survey a wildlife market to how to organise protests” she says on the two years she spent working for NGOs. “It was very useful to have that chance”

Shortly after Astrid completed her pangolin project, by a lucky coincidence, a professor working at HKU at the time read a press release for it. Impressed by her passion and experience, he invited her to meet with him about doing an MPhil –a year-long Masters program with the possibility of continuing as a PhD– on the trade and ecology of pangolins in Hong Kong. However, Astrid was hesitant given the difficulty of researching such a rare and elusive species in the wild. So, the professor instead suggested a different one to focus on:

“He suggested that the cockatoos might be a good model species for the issues that I’m interested in related to wildlife trade” she says. “They’re here because they’re traded as exotic pets. They are overexploited in their native habitat and they’re surviving in an introduced urban environment, which is an increasingly common phenomenon that we see across urban centres which are central to wildlife trade networks.”

There was also a real need to study them given that their species is critically endangered in its native Indonesia, making any individual population potentially vital for their conservation. Yet aside from one study done by the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), almost no comprehensive efforts had been made to study the yellow-crested cockatoo population of Hong Kong before.

“Other than that [CUHK study], there was only very sparse information in the bird guidebooks of Hong Kong” says Astrid. “My study and the CUHK team’s were the first proper research to have been done, aside from the AFCD having done a few roost counts in the past.”

Recognising this knowledge gap and the potential value of filling it, Astrid decided that the time was right to return to academia. So, she accepted the professor’s offer and finally began her long-awaited career as a conservation biologist.

The PhD Years

Astrid’s PhD focused on two things: the trade of yellow-crested cockatoos in Hong Kong and the ecology of the local population. But with very little pre-existing information on either topic, she faced the somewhat daunting task to having to gather it all more-or-less from scratch; sometimes even having to develop new techniques to do so.

Ecology

Given the multiple facets of species ecology –population, behaviour, resource availability etc.– understanding that of the Hong Kong cockatoos required a multi-pronged approach.

To assess the state of the population, Astrid looked at past trends using records by the Hong Kong Birdwatching Society going back to 1964. She also organised groups to survey major cockatoo roost sites in the early evening (when the birds fly in to roost for the night) and record how many they saw within an hour. When taken all together, this data allowed for an estimation of the total current population size.

When it came to resources, Astrid took note of the plant species she saw cockatoos eating and collected samples whenever possible. She also took note of any tree cavities she observed cockatoos nesting in and the species of tree to estimate the availability of breeding sites in Hong Kong. As an added bonus, Astrid got a grant from National Geographic and the Ocean Park Conservation Foundation to study the largest remaining population of yellow-crested cockatoos in Komodo National Park, to compare the behaviours and ecology of those birds with the ones in Hong Kong.

Wildlife Trade

In 2002, the yellow-crested cockatoo was listed under Appendix 1 of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES), thus illegalising the trade of wild-caught individuals. But it does not illegalise the trade of ones that are captive-bred within the country of sale and the species remains a common sight in bird markets and pet shops in Hong Kong. This loophole potentially provides a cover for wild yellow-crested cockatoos to be laundered alongside captive-bred ones. But historically, there has been no way of telling which ones are which.

To address this, Astrid turned to forensic science and alongside her PhD supervisor, Dr Caroline Dingle, developed a technique to differentiate between wild and captive-bred cockatoos using an aspect of the cockatoo’s biochemistry. Namely the ratio of carbon isotopes in their feathers.

The carbon isotope ratios (13C/12C) of an animal’s body often heavily reflect those of the foods it eats. As wild cockatoos eat mainly fruits and flowers and captive ones eat seed and man-made pet foods, their carbon isotope ratios should differ significantly. To test this, Astrid collected feathers from both wild and captive cockatoos and compared their carbon isotope ratios to those of the foods they were eating (hence why she collected samples of their food plants) to see how much they matched.

Discoveries and Insights

So, what did Astrid discover about the long under-studied cockatoos of Hong Kong? As it happens, quite a lot.

To begin with, she found that this population numbers around 100-150 birds, roughly 6-7% of the global population. This makes them vital not just for their species’ continued survival, but potentially for future reintroduction efforts in Indonesia. “This provides an opportunity for Hong Kong to play a role in the conservation of this species going forward” Astrid comments. She also found that wild and captive-bred cockatoos do indeed have very different carbon isotope ratios, and the techniques she developed to test this potentially provide a powerful tool for authorities to properly monitor the cockatoo trade in Hong Kong. “That tool could be used, in combination with a number of other tools, to test whether birds in the market had come from the wild or were captive bred.”

However, the study also revealed that the Hong Kong population, while not in decline, is showing little signs of growth, which Astrid concludes to be due to a lack of nesting sites. “We found that the cockatoos in Hong Kong are limited in their reproductive capacity because there are not enough large-diameter trees that provide the cavities that they use for nesting” she reports. The cavity-bearing trees that do exist sometimes get damaged in typhoons, potentially exposing vulnerable young chicks to predators like snakes and civets

Soaring Ahead

Of course, some people may still be asking: ‘Why should we care about these cockatoos? What benefit is it to us to protect them?’ Astrid’s answer is simple:

Hope.

In a world where countless species are being driven to the brink of extinction and beyond by human activities, it seems inconceivable sometimes that any wild animal, much less a critically endangered one, could manage to hang on and coexist with people. And yet here in Hong Kong, this crowded concrete jungle that is so unlike its native habitat, a bird that is almost extinct has done precisely that. For Astrid, that fact alone is reason enough to conserve them, particularly now when the news is dominated by apocalyptically bleak environmental stories.

“We living in Hong Kong should value [these cockatoos] for the hope that they represent. That humans –even in such a densely populated and hyper-urbanised environment– can coexist with wildlife, and that even critically endangered species that are threatened elsewhere can find a safe haven in our urban parks.”

Encouragingly, Astrid and her fellow conservationists may not be alone in feeling this. During her PhD, she conducted a survey that found a significant level of appreciation for the cockatoos amongst people living around their habitats, though not a great deal of knowledge about them. To Astrid, this is a sign that, with the right education campaign, the public support essential for successful conservation could easily be generated amongst Hong Kongers. “I feel that many people in Hong Kong would find it interesting if they knew that [these cockatoos] were critically endangered and are flying around their offices and homes in Central or Pok Fu Lam” she remarks.

As for her PhD itself, she hopes that it can drive and inform efforts to boost the cockatoo population, like increasing the number of nesting sites for them. In the short term, this can mean erecting artificial nest boxes. Longer term, it means protecting the –mostly slow growing– tree species that cockatoos use for nesting, many individuals of which aren’t yet large enough to form cavities (possibly due to Hong Kong having been heavily deforested until relatively recently). Protecting them could provide cockatoos with extra nesting sites in the future, as well as benefit a myriad of other species that depend on them.

Lest you think Astrid plans to take a break now however, think again. Even after five years of intensive hard work, she fully intends to keep the momentum of her research going. Hence her upcoming postdoctoral project on cockatoo genetics, which aims to determine whether inbreeding (a common problem in small populations) is affecting population growth, among other things.

“The thing about PhDs is that at the end of the 5 years, you are really starting to get your momentum going and you’re really starting to get into the question. It takes a while to warm up and that’s why we want to continue this research, because even though we’ve answered some questions, more pop up.”

Curiosity isn’t the only thing behind Astrid’s drive to keep going. Earlier this year, she gave birth to her first child, Agnes, and the desire for her to have a safe, prosperous and beautiful world to grow up in has only strengthened Astrid’s resolve to do her part to tackle the ecological crisis. “Having a daughter now really emphasises this” she says. “I want the world to not continue down this path of destruction that it currently is on.” She recognises that, even with her expertise and connections as a conservationist, she herself can only play a small role in addressing that. But to her, that is no reason to be discouraged. If anything, it is all the more reason to carry on and encourage others to join in, especially those who feel powerless to act.

“People are always saying ‘I can’t be bothered to recycle. I can’t make a difference.’ Maybe not, but why not do it? Why not just try and apply yourself to saving the planet? Because it’s very important to all of us and our future and our children’s future and the survival of species that have evolved over millions of years.”

And what about those who want to do more? Those who really want to apply themselves by dedicating their careers to protecting the wondrous species that share our planet? What advice does Astrid have for them? Simply put: be passionate, proactive and willing to do and try anything.

“Any skill that you have –be it creativity, communication, organisation, anything– you can apply that skill to your passion and if you do, the money will follow and that will enable you to keep going. Volunteer, network, just apply your energy towards getting to your goal and you will get there.”

Before you go:

To learn more about Astrid, visit her website here: https://earthsavio.com/astrid/

Finally, here are a few quickfire questions and answers to help you get to know Astrid better. We asked her to say the first thing that came to mind when we said the following words. Her responses are in italics.

Cockatoo: Clever

Hong Kong: Urban

Wildlife Trade: Shark Fin

Journalism: Interesting

Passion: Wildlife

Indonesia: Beautiful

PhD: Challenging

Hope: My daughter (Agnes)

Purpose: Survival

Future: Hope

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Thomas Gomersall

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social media for daily news, competitions, and more.