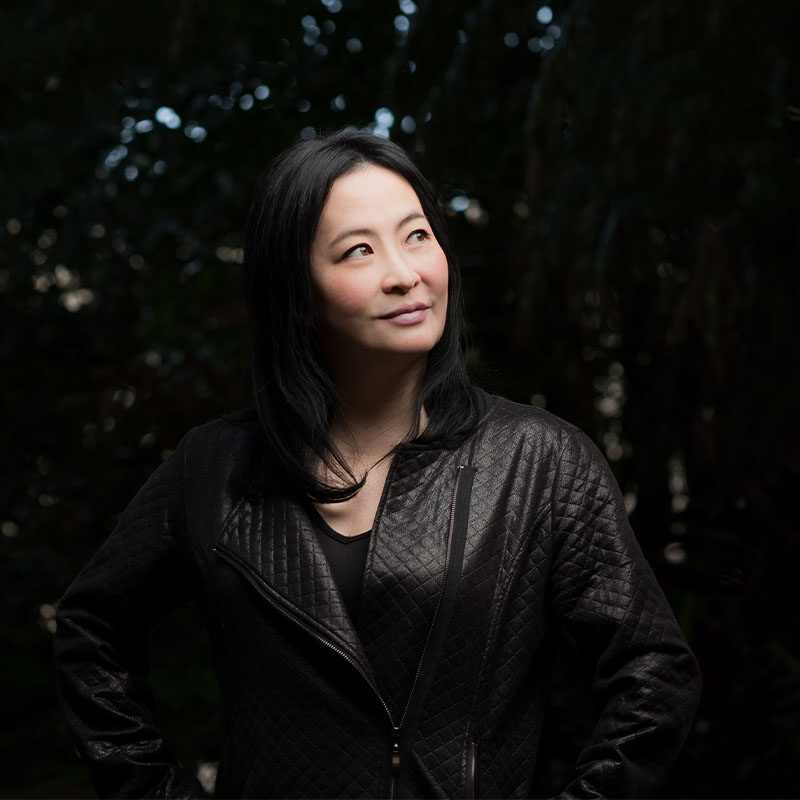

Craig Leeson: Filmmaker Intent on Jolting Humanity into Action (before it’s too late)

On a bright morning in Paris, France, Craig Leeson sits down at his kitchen table and pops open his laptop to check his email. He has many things to get to; from responding to inquiries related to the charities and NGOs he works with, checking in with colleagues from his film studio in Hong Kong, to planning the itinerary for a trip to the US to put the final editing touches on his upcoming documentary The Last Glaciers. Such a heavy workload is old news to Craig. In fact, he prefers it that way. The way he sees it, his work is an expression of his life’s purpose – to open the world’s eyes to the environmental calamity human behaviour is causing and encouraging positive change. Time to sit idle is a luxury he (and humanity) cannot afford.

Scrolling through his inbox, Craig comes across an email from an old friend, I thought you would like this, I have no idea where she picked this up! the message reads. The link in the email takes him to an Instagram video post. In it a two-year-old girl (his friends’ daughter) peers into the camera. “I’m going to be vegan and grandma shouldn’t use straws because it hurts the fish,” she confidently squeals. Craig sits back in his chair and smiles. If only the rest of the world were as perceptive and passionate as his friend’s daughter, protecting our fragile eco-systems may be a less steep challenge. But Alas, many people who run our governments and businesses are mainly detached from the truth about our perilous situation on planet earth. In the last 40 years, humanity has kept its head buried in the sand while we have lost over half of the world’s biodiversity. Unless dramatic change takes place, we are passing through a series of one-way doors that lead to our ultimate destruction.

In this WELL, WHO exclusive we profile Craig’s journey to remove the blindfold of indifference over humanity’s eyes. From a young lad playing in the waves of his native Burnie, Tasmania, to his experiences travelling the world as a journalist and filmmaker, Craig has evolved into a voice we can (and should) trust. With a talent for connecting to all types of people and a flair for an adventurous life- from being in a rock band, to flying planes in Miami, just to name a few – Leeson’s story is one any young adventurer is sure to enjoy and aspire to. His advice for harnessing purpose and reframing our “heroes” provides an opportunity for us all to rethink our relationship with the natural world and our role in it.

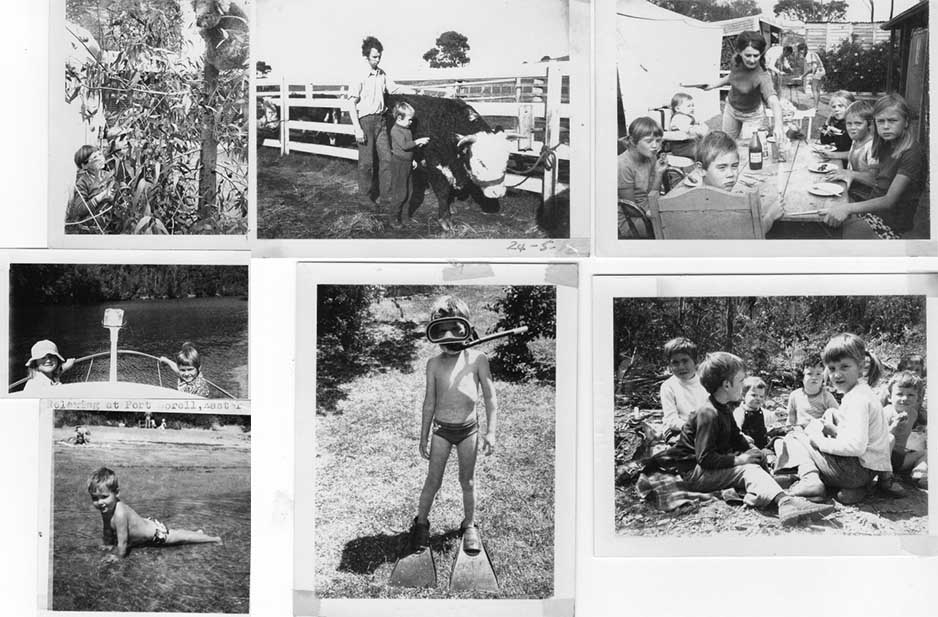

Surfs up- A childhood in Tasmania

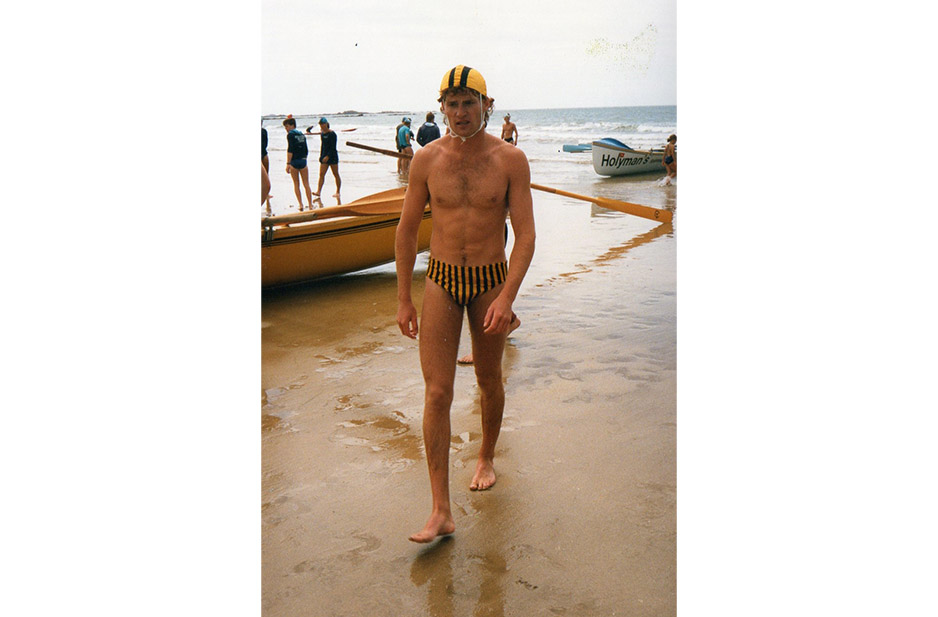

It should come as no surprise that Criag’s bond with nature was forged at a young age. He spent his childhood exploring rock pools and surfing waves in his hometown of Burnie, Tasmania, a beachy town of only 30,000 people. Growing up Craig enjoyed attending his local school – after all it was opposite the beach – but his passion for playing outside was consuming. “My friends and I found a drainpipe that led from the school football field, under the highway and to the sea… We would escape class by crawling through the pipe to our freedom. Only thing you had to watch out for was the penguins who pecked you along the way,” he reminisces. Long hours outside with his friends were coupled with his mother and siblings at home, tending to a host of wild animals they cared for in their large backyard. His time caring for animals, which included a vast array of birds, mammals, reptiles, and other small creatures, built his appreciation for the living world. Craig’s mother, who helped Craig and his siblings tend to the animals, nurtured his sense of caring and appreciation for all creatures. “My empathy was really developed and encouraged by my mother – a strong woman but incredibly caring,” he remarks. When Craig was not outside surfing or tending to the host of creatures in his yard, he was inside watching nature documentaries by the likes of his childhood hero David Attenborough. “He was such an influence on me growing up… watching his films was a way of travelling to see amazing animals without leaving my house,” he remembers.

Towards the end of schooling, he was intent on starting his career as a professional life saver- enjoying more time in the ocean surfing and hanging out with his friends. His father, however, convinced Craig that while fun, being a lifesaver was not a practical profession to build a career around. “He sat me down and encouraged me to focus on something more serious… He suggested being a journalist.” And why wouldn’t his dad suggest as such? Journalism after all runs in his family’s blood- three generations of Leeson’s preceded him in the media space. Heeding his dad’s advice, Leeson joined his local newspaper, The Advocate Newspaper, where he reported on what he knew best- the ocean, sports and the people that ran the local community in Burnie.

Journalist journey- from print, radio and then tv

Early in his days as a journalist Leeson broke a story that would cause a tremor in the local community, eventually shaking its way onto the national stage in Australia. Leeson had noticed an uptick in pollution in the waters he and his friends surfed. “You would get out of the water and your eyes would be bright red and stinging from something in the water,” he remembers. After conducting research and having samples analysed in a laboratory, he wrote a story that revealed the source of the chemical imbalance in the water- high level of organochlorines and dioxins were being expelled into the water from the town’s industry, which included a paper mill, an acid plant, a paint pigment plant and a slaughterhouse. When he confronted the State government about the issue, it admitted to the problem; a problem it had been hiding from the public. Due to the outrage caused by the story, the government took action to halt dangerous run-off from entering the ocean, introducing a host of policy changes still active to this day. “It was then I learned the power of the media,” Leeson reminisces.

Four years after entering and climbing the ranks of print journalism Leeson moved into a new role, reporting the news on the radio for ABC in Tasmania. Leeson was drawn to the pressure of reporting live on-air and having to perform on the spot. “I’ve always thrived in that environment… I like the pressure of it all,” he remarks. A few years later Leeson moved to become a tv reporter and later anchor for the nightly news, a program broadcast across his home state. Honing presentation and story-telling skills propelled Craig’s career forward. As his dad predicted, journalism was a profession that Craig would thrive in (even if at first, he wasn’t so sure himself.)

After reaching a level of notoriety in Tasmania and greater Australia, Craig’s thirst for adventure led him to Hong Kong, to cover the handover of the territory to China. He had been drawn to Asia by travels in China and was keen to take on an assignment in the region. “Hong Kong at the time was a special place…The energy was electric…with interesting people from all of the world,” Craig comments. He was most drawn to interacting with people from a wide array of backgrounds. While he remembers the large expat community, he also was drawn to the humour and fellowship from local people. “I remember my first typhoon. When the signal no.8 flag was hoisted that meant you couldn’t move anywhere, and I spent the next 8 hours locked down in a bar with police and government officials. By the time the typhoon was over we were all well lubricated. I learned

After revelling in his time reporting stories across the Asian region for a tv current affairs programme called Inside Story, and news anchoring in Hong Kong for Asia Television, Leeson was drawn to cover the developing story of the fall of Indonesia’s president, Suharto. He took a flight to Jakarta and spent the next two years covering the mayhem that followed, which eventually led to the East Timor war, which claimed the lives of many, including a good friend and fellow journalist who lost his life covering the conflict. Leeson’s comprehensive coverage of the fall of Suharto won him further respect as a journalist and an award from the New York Film Festivals for the international documentary category.

After a sabbatical in Florida, US, where he spent a year learning how to fly planes, Leeson returned to Hong Kong in 2002. He was drawn, among other pursuits, to try his hand at long-form storytelling. “90 seconds of reporting in the field is not enough to tell a comprehensive story that can touch the viewers in a deeper way,” Craig points out. “I learned the beauty of long form story telling in my first full length documentary covering the travels of Marco Polo for National Geographic Asia,” he reminisces. The process of interviewing a wide range of people, travelling to a variety of locations, and tying in a narrative was a format that leveraged all of Craig’s strengths. The documentary went on to win a series of accolades, being voted the 13th best documentary of all-time on National Geographic Asia. With the success of the film, Craig had validated his passion for long form story telling resonated with a larger audience.

A Plastic Ocean

Leeson’s first company Ocean Vista Films (named after the beach he grew up on) grew from strength to strength, making documentaries, tv series and corporate films for the world’s biggest brands and broadcasters. The topics he covered were varied but he found himself turning back to the ocean at every opportunity, with documentaries focusing on the destructive fishing practices in Asia, the plight of Hong Kong’s pink dolphins and other environmental films. But Leeson’s animal passion since a child has been whales, particularly blue whales. Weighing as much as thirty elephants and growing as long as three school busses, Leeson had always wanted to use the film to educate the world about the species, illuminating the wonder of their lives humans know so little about. His opportunity came when a good friend and marine biologist who had worked with David Attenborough brought an issue to Leeson he knew very little about – single use plastics. Recent evidence from a sailor had demonstrated an abundance of plastics swirling around in a large current in the north pacific and it appeared our oceans were being choked with the stuff. Further research by the producers demonstrated that these plastics were causing massive problems to marine creatures, including whales, and Leeson wanted to find out just how bad the problem was. After securing funding for the project, the documentary team set off first to the coastal waters of Sri Lanka, where Leeson and his crew hoped to capture the whales on film. In addition to capturing rare footage of blue whales in their natural habitat, the crew hoped to conduct research so marine biologists could better understand blue whales’ movements, health and population trends.

After weeks of searching the seas- an expensive and time-consuming endeavour- the team had seen many whales at distance but where unable to get close enough to film. The blue whale, despite it’s size, was proving to be as elusive as its reputation. But luck was on Leeson’s side. On the final day of filming, as they head back to port without the footage they had hoped for, there came a cry: “blow!”. Leeson had refused to pack up the cameras, which were ready to go and in the water in minutes. What they came across was truly astonishing- a family of pygmy blue whales, a slightly smaller cousin of the blue whale, relaxing on the surface of the ocean. Among them, a curious and sociable juvenile whale swam about exploring the divers as they got closer. Craig, directing the crews from the surface of the ocean, saw the juvenile approach him and dived down to get a closer look. After a few minutes of observing the 15-meter long “baby” of the group, the whale turned on its side and let out a massive cloud of whale poo – “it was a poonami”, he remembers – in Craig’s direction. Surfacing for air, Craig bumped into one of his cameramen who was laughing hysterically. “Mate, you’ve just been pooed on by the rarest animal on the planet!” he exclaimed.

The magical time spent with the pod of whales was a dream come true. The crew collected as much data as they could (including of course samples of whale poo) to be taken back to shore for analysis. There was, however, a very sour note to otherwise amazing experience. Just a short swim away from the whales was a worrying sight- large clumps of floating plastic waste. “It was absolutely dreadful- everything from plastic bottles, lighters, packages of all shapes and sizes. And this is where the whales were feeding,” recalls Leeson. Craig and his crew asked themselves, how could such a pristine environment in the distant seas be littered with so much debris? What affect was this waste having on the lives of the whales and the other creatures that sustained their eco-system?

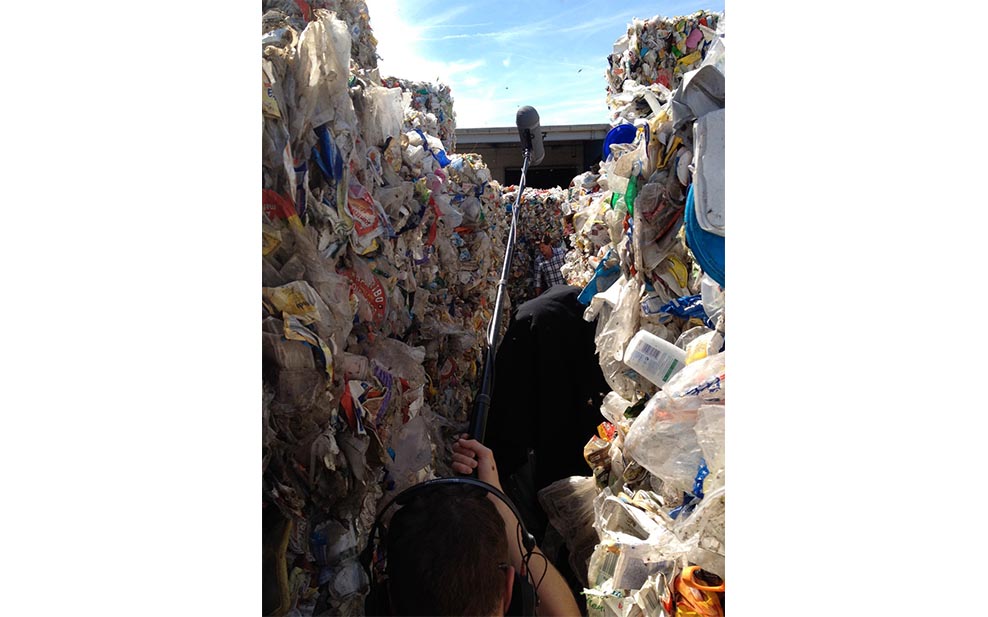

Returning to shore, the sight of the plastic floating around the whales stuck with Craig. “I thought to myself, how could someone not as connected with the ocean as me know what was going on with plastic pollution.” That shoot galvanised the team, which set off on a world-wide tour of ocean environments, travelling to over 20 countries, from beaches of the remotest of islands to the depths of the deepest seas.

What they found was shocking- man-made plastic waste was everywhere they ventured to. And where plastics were not visible, they were still usually present in the form of micro-plastics. The vastness of the issue was beyond worrying. “What we didn’t know is that it was coming up the food chain… we started asking questions about the effects of plastics on human health,” Leeson comments. Always interested in the human side of the story, Craig went to the communities that were most affected by plastic pollution and interviewed the local inhabitants. What became clear is that underprivileged people, in places such as Tuvalu, Indonesia and Pier 18 – near the trash heap known as “Smokey Mountain” in the Philippines – are most vulnerable and suffer the harshest consequences.

The numbers the film highlights are mind boggling. 8.3 billion tons of plastic has been produced by humans, 6.3 billion tons of which has become waste. Only 9% of the 6.3 billion tons has been recycled. At such scale it is hard to know exactly how much of that plastic ends up in our oceans, but it’s estimated that there are over 5 trillion pieces of plastics littering every part of every ocean on the planet, over 70% which we cannot see as it’s on the ocean floor. In just the past 40 years it is estimated the earth has lost 52% of its wildlife, plastics undoubtably playing a role.

Often overlooked are the consequences biodiversity loss and toxification of the environment have on humans. Since A Plastic Ocean premiered, there have been a host of frightful studies published showing how toxins in plastics have crept up the food chain. It is estimated that humans consume 20KG of plastics in their lifetime– enough to fill two large recycling cans. One recent study points to a dramatic loss in sperm counts across the human population. Scientists suggest at such a pace human sperm counts could reach zero by 2045.

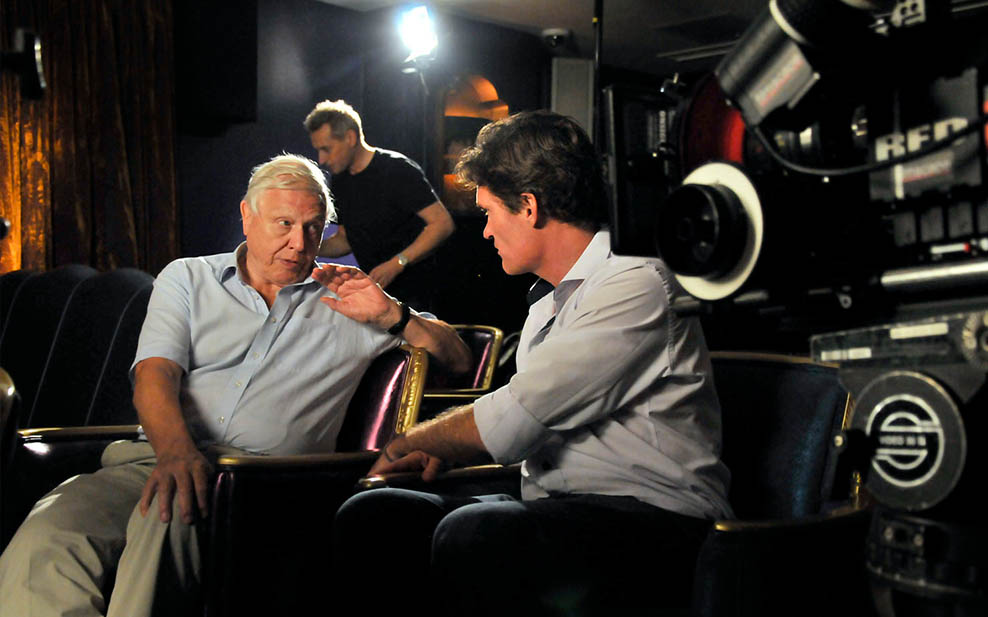

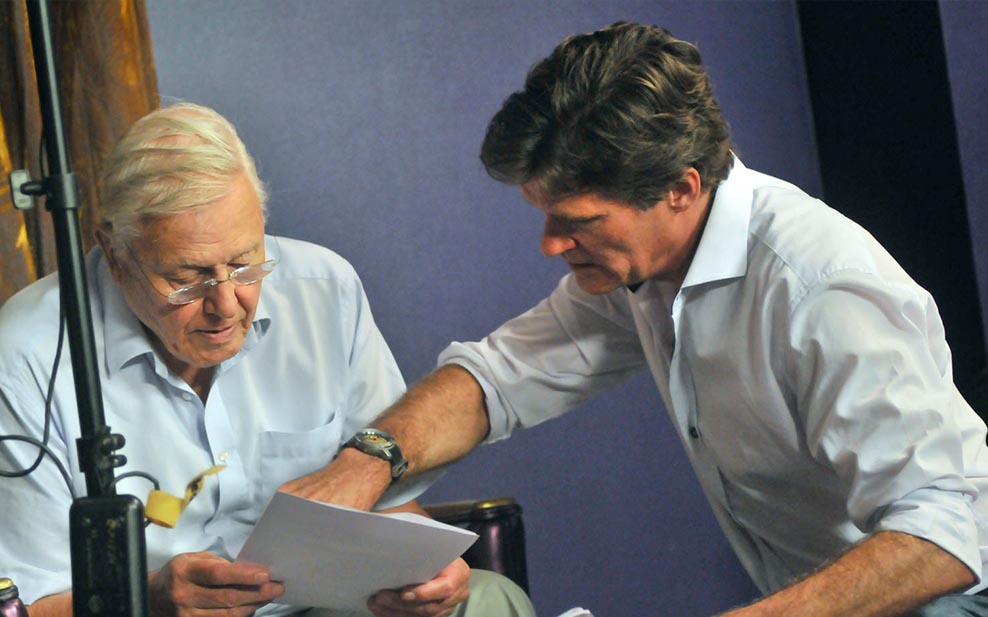

While there is still much work to be done, the intended impact of the film- to educate humanity on the crisis at hand and inspire change- has hit home. “The message of A Plastic Ocean has reached far and wide,” says Craig. Since the filming comments have poured into Craig and his team. Even Leeson’s childhood hero David Attenborough, who appears in A Plastic Ocean, called the film “the most important film of its time.” “Following A Plastic Ocean, he took the message into his other films- starting with Blue Planet 2,” Leeson says.

The film has inspired change on many levels. “It has had an affect on people of all levels of society,” Craig points out. Take for instance the story of the minister of environment in Chile, who met Leeson during filming. “He and his wife both watched the film and both cried. They woke up the next morning and his wife asked him “why don’t you go to work and do something about this,” Leeson tells. Almost immediately the minister pushed through reform banning plastic bags along the coastline of Chile, an action followed by later administrations who expanded the banning to a national scale. The story is just one example of how the film’s impact on one person can result in larger scale change.

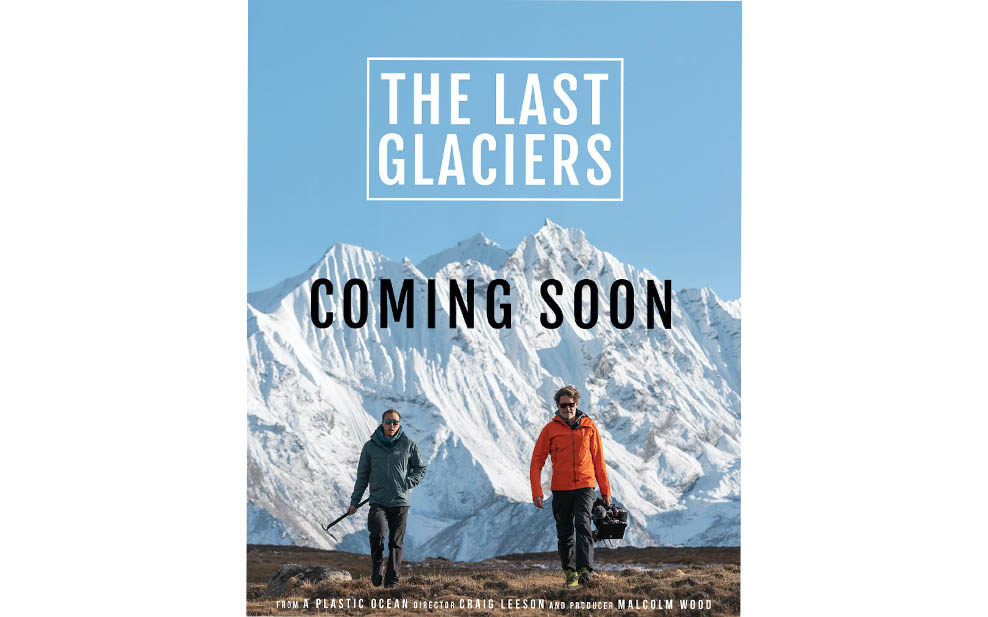

The Last Glaciers

Leeson’s next film, a film focusing on the loss of the planet’s glaciers, hopes to achieve (perhaps surpass) the impact of A Plastic Ocean. Filmed over 4 years in 12 different countries The Last Glaciers promises to deliver the same style of story-telling viewers have come to appreciate from a Leeson Media produced film.

Similar to the background of A Plastic Ocean, Leeson learned of the peril of the state of the world’s glaciers in an inadvertent way. Invited to train with his good friend Malcom Wood in the French Alps for a planned climb of Everest, Leeson arrived when the area was experiencing an especially warm bout of weather. The glaciers and snow they were supposed to be trekking on simply were not there- they had melted away. Researching the causes, he knew there was a story to be told. With the help of Malcom, a world-renowned adventurer and paraglider, they put together a plan to dive into the subject and capture amazing footage of the natural wonders still left.

Ice caps and glaciers are often not at the forefront of most people’s minds. However, they cover 10% of the land area on earth and store vast reserves of fresh water. In our interconnected world, if we continue to lose ice to melting, the outcome will be catastrophic. “We are approaching the point where it will be too late… they are called tipping points for a reason,” Leeson states.

Illuminating issues such as plastic waste and the melting of the world’s glaciers is not just about education- it’s about changing behaviours and inspiring change. “The Last Glaciers really is a film about the legacy we are leaving for the next generation,” Leeson points out. “In the third act of the film we present solutions on an individual level, how we can reverse the damage before it’s too late,” he explains. “And that’s important. Because recognition of the problem comes from awareness. But for immediate and effective solutions we need systemic change and that means re-engineering our economic model to value nature capital as our most important asset, not oil, gas and coal, which contributes significantly to the crisis. For that to happen we need effective corporate and governmental leadership.”

A Call to Action

Leeson hopes his films and the messages they deliver help pull humanity back from the brink. It is going to the take collective effort from government and businesses to shift their way of operating. Such grander change is not possible, however, without the individual awareness he seeks to create through his films.. While it is easy to despair in the awful trends, taking action is the only way to make a difference. “There are so many ways that individuals can now change the narrative through their actions… it’s important that people realize they have the power to actually do something about it. There is no point in sitting on your couch and forwarding other people’s messages on your social media. Get out there and take action… Demonstrate the change you want in the world,” says Leeson.

To Leeson there is a true power in people finding purpose. “It’s so powerful to know your actions do have an effect…. It really does give you a sense of purpose,” Craig quips. There are many avenues he suggests, but “becoming a smarter consumer is the starting point.” There are a host of actions you can take, for example, from putting your money behind investments that are divesting from oil and gas, supporting brands with sustainability and purpose in their products, gathering friends to petition local stores to make changes in their recycling policies, and insisting that your home or office space operators provide policies for waste removal and power utilization. Often out of mind for young people is the basic right to get involved in your community politically, to run for local council and pass legislation that protects the environment.

To Leeson, the notion of continuing down the path humanity is on is pure madness. “Demanding infinite growth from finite resources is brain damaged thinking,” Leeson explains. Craig firmly disagrees with conservatives decrying the effect of stress caused by worrying about the environment. He wears this stress constantly with what he sees and films. The idea, after all, is that we should feel anxious. “Eco-anxiety can be a powerful tool. We must use it to focus on action. We are going to have a lot more to be anxious about if we let the earth heat to 3 degrees above pre-industrial levels by the end of the centure,” he says.” But Leeson doesn’t believe the anxiety is equally distributed. “What I believe IS unfair about eco-anxiety is that we’ve created this situation for the younger generations… it’s important that we provide kids with tools to make changes and that we provide them with an outlook on their future that is positive by the changes we make now to protect their futures,” Leeson suggests.

Leaving a Legacy

After “The Last Glaciers” is released in 2021, Leeson plans on thinking about his next endeavour. “Before one project ends, you are always thinking what’s next… there are so many stories I want to tell,” he explains. What has made his projects so successful is they usually come to him, not the other way around. “These things come to me and tap me on the shoulder and say, “hey you need to pay attention here,” Craig explains.

Leeson hopes the stories he shares with the world will be looked back on in appreciation. Taking inspiration from his heroes David Attenborough and Australian environmental advocate and former Greens senator, Dr. Bob Brown, he views the journey of change-making as a long-term process, not one to be deterred by negative criticism or personal attack. “Our environmental heros are able to rise above the personal attacks and see the importance of being dedicated to causes bigger than themselves,” Craig observes. Hopefully, in time, the contributions of true “change-makers” will be recognized on a grander scale, replacing some of the more superficial heroes of today.

Beyond any form of recognition, inspiring change, especially with future generations, is what Craig views as the most important aspect of his work. The more positive inertia his work can create in the world the better- no matter what the narrative is that surrounds it. It comes down to shifting more attitudes through education. “With knowing comes caring, with caring comes change,” Leeson quips. It’s up to all of us to take his cue.

Before you go:

To learn more about Craig and his mission check out

Make sure to watch A Plastic Ocean- Available on Netflix and iTunes and Amazon

Keep eyes peeled for the release of The Last Glaciers later this year

To learn more about how you can support the mission of A Plastic Ocean in Hong Kong, check out http://www.aplasticocean.foundation/

Or globally with www.plasticoceans.org

Cover photo Credit: William Furniss (@WilliamFurniss)

To read more WHO? Exclusives with inspiring leaders click here.

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Jackson Kelleher

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social for daily news, competitions, and more.