Sidhant Gupta: Inventing Technology to Forge a Better World

From our earliest days, we humans have always been an innovative, technological species. From the simple stone tools of our Ice Age ancestors, we have gone on to invent the wheel, the combustion engine, electricity and the internet, among many other things. This technological savvy has allowed us to shape the world to our needs, turning our species from a group of bipedal primates in prehistoric Africa into a dominant global force today.

But just as technology has empowered us to make positive changes in the world, so too has it enabled the negative ones we’ve made. The same Industrial Revolution that supercharged our technological capabilities –particularly the ones related to burning fossil fuels– was also a root cause of the climate crisis. And let us never forget the horrific potential of the nuclear weapons stockpiled around the world.

Without action, humanity faces a grim future. To avoid it, we must start using our ingenuity to fix the world before it is too late. And while much of the transition to a sustainable future will involve political reform and individual lifestyle changes, the important role that technology will have to play should not be dismissed.

To fuel this new technological revolution, the world’s brightest minds must shift to coming up with solutions that benefit the planet. Someone doing just that is young inventor and entrepreneur, Sidhant Gupta. At just 25-years-old, he already has an impressive list of achievements to his name, including two record-breaking robots and two start-up tech companies. Though his journey began as a quest for personal satisfaction, it has since become a purpose-driven mission to harness the power of robotics to save our oceans. Whether it’s improving how we conduct field research or how we clean up plastic, Sidhant is literally re-inventing marine conservation, one new gadget at a time.

In this WELL, WHO? Feature, we share Sidhant’s story, from tinkering with robots as a child, to studying engineering in Hong Kong and becoming a budding tech entrepreneur. We hope his accomplishments prove that the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) need not herald a Terminator-style robot apocalypse, but a faster, more efficient path towards a thriving future for our planet.

Boy Inventor

Sidhant’s fascination with technology stems from his childhood in Bangalore, India, where his parents ran a small company manufacturing metal components. Watching these products being made, Sidhant was inspired to build things of his own, starting with Legos but then moving on to electronics. In middle school, he learned how to code software and combined that with an interest in AI to create his own robots. “At that time, my goal was just to build a walking robot. I just thought it would be a cool project to do” he says of one that he built at 16.

That particular robot would prove to be life changing for Sidhant when, on a whim, he entered it into the Indian national record book. To his surprise and delight, it ended up breaking the record for smallest robot. More than that, it made him realise that his childhood hobby could lead to far bigger things than he’d ever imagined.

“The very first robots I built didn’t have any real major purpose. That’s why I think of that event as an inflection point, because after I got a national record, it suddenly felt like I [could] do so much more with this stuff” he recalls.

From there, he went on to earn a computer engineering scholarship at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) in 2015. As well as wanting to study in a new city, he was drawn to HKU’s robotics scheme, which he felt would significantly increase his knowledge in the field.

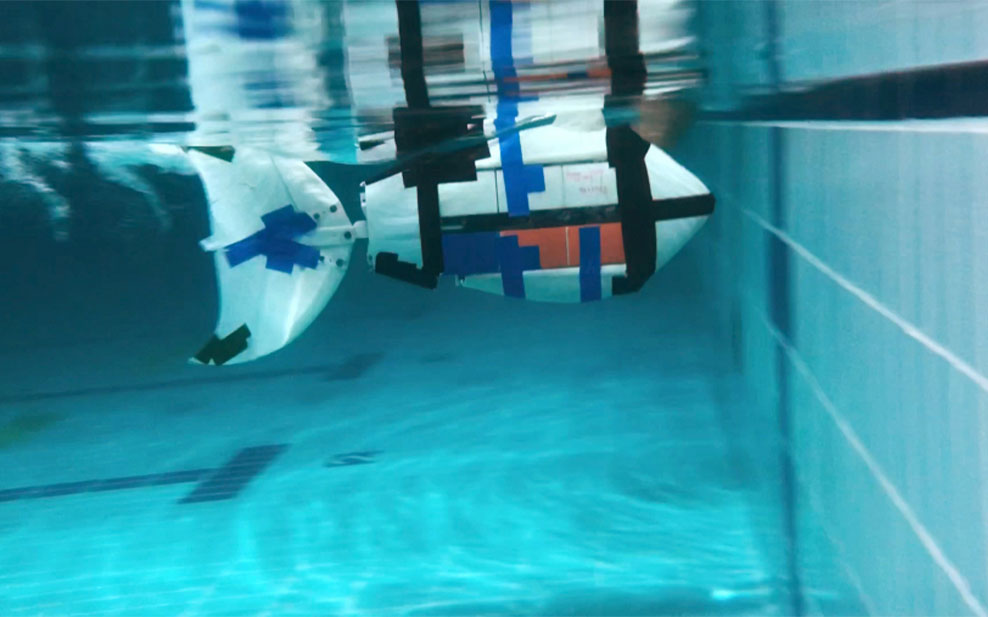

Becoming a record breaker once had given Sidhant a thirst to do so again. During his time at HKU, he spearheaded the VAYU Project to build the world’s fastest robotic fish. At the time, this was boundary-pushing work, as almost no research had been done on replicating the highly efficient undulatory movements of fish for marine propulsion. As a result, he received plenty of funding and support from HKU. “We said, ‘Here’s a cool opportunity to break a record, but also to push research into a new field.’”

After nearly 5 years of work, the VAYU Project fish netted a Guinness World Record in January 2020 for fastest robotic fish, completing a 50 metre swim in 26.79 seconds and beating the world records for women’s breaststroke and backstroke. “It felt amazing!” says Sidhant “It made me realize that however big the dream, given enough effort and commitment, you can make it real!” More importantly, the VAYU Project also gave Sidhant experience in building complex marine sector robots, which would serve him well later in his career.

An Inventor Abroad

For Sidhant, another perk of attending HKU was the opportunity to go on overseas trips subsidised by the university (service learning trips). In exchange for having their trips subsidised, students were required to do something useful for local communities in their destination countries. To Sidhant and a couple of friends, this seemed a fair deal for an expenses-paid holiday. “They started off with kind of a greedy, self-interested premise” he says half-jokingly of his service learning trips. “We just wanted to travel and we said ‘Hey the university has these funds to pay for air tickets. What do we need to do?’”

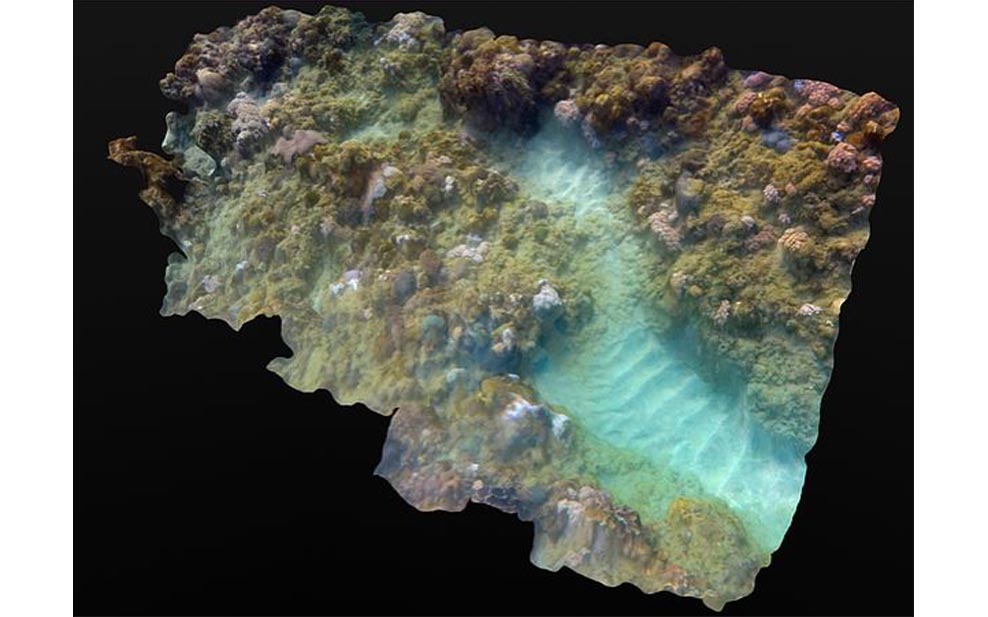

The answer was reaching out to various local organisations to offer help in addressing problems in their communities. During Sidhant’s first service learning trip in 2016, he provided video-based learning to a school in rural Vietnam. But on subsequent trips, his efforts focused more on marine conservation, starting with a collaboration with inventor and environmentalist, Cesar Harada, on a coral reef mapping project in Mindoro in the Philippines.

Properly understanding the global scale and severity of coral bleaching requires having detailed, regional-scale maps of individual reefs to measure the extent of the damage bleaching does to them. However, such detailed mapping does not exist for many reefs, particularly for more remote ones like those at Mindoro. “The truth is, we don’t actually know how bad the damage is” says Sidhant. “The challenge is that you can’t scale up the research [manually], because there’s only so many researchers who know how to do this.” Cesar wanted to develop replicable technology that could map reefs automatically (read: more efficiently). “The idea was if we take out the manual process and can make it automated to map reefs, maybe there’s an opportunity to scale this up.”

Armed with the knowledge gained from working on the VAYU Project, within a week Sidhant and his friends assembled the Mindorobot: a floating remote-controlled robot that scans and photographs reefs in great detail. Not only was the prototype they built easy to use, it was also easy to assemble and required no costs in manpower salaries, allowing the local people to easily and affordably map their local reefs themselves. Seeing first-hand the difference his work had made also made Sidhant realise the positive real world impact his talents could potentially have.

“My experience working on Mindorobots with Cesar was really life changing in the sense that I realised that I had the opportunity to make a real difference” he reflects. “I [realised] that I have the technical skills, so why don’t I do something that can change the world?”

After that, he started networking more with marine conservationists for his service learning trips and inventing new technologies to solve the problems they faced. Technologies that would form the bedrock of his career after university as well.

SeaTech

After graduation, Sidhant briefly worked as an entrepreneur-in-residence for a software company in Myanmar. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic sank that company, he was forced to return to Hong Kong in an opportunities-scarce job market.

Unfazed, Sidhant decided to create his own job opportunities by selling the technologies he’d previously invented on his service learning trips. After all, the problems they were created to solve were widespread within marine conservation and he knew there were clients eager to make use of them. During his time in Myanmar, he had also gained valuable insights into how to start a company (or several). “ When it came to starting a company, we already had this ready-made network and a product. [I was] like ‘sure I can make this work’.”

To earn some money to get started, Sidhant and his team offered their services and expertise to players in the marine conservation world. One of their first projects was helping to develop a phone app called “Saving Face” –now available for download on android and iOS– to scan and track the facial markings of an endangered fish in Hong Kong’s live seafood restaurant tanks: the humphead wrasse. Sidhant’s app was designed for users to scan humphead wrasse in restaurant tanks to check for illegally imported individuals – a vital step in combatting the overexploitation of this species.

Later, once they had amassed the needed capital, they founded two start-up companies specifically to revolutionise how we study and protect our oceans: Open Ocean Cam and Clearbot

Open Ocean Cam

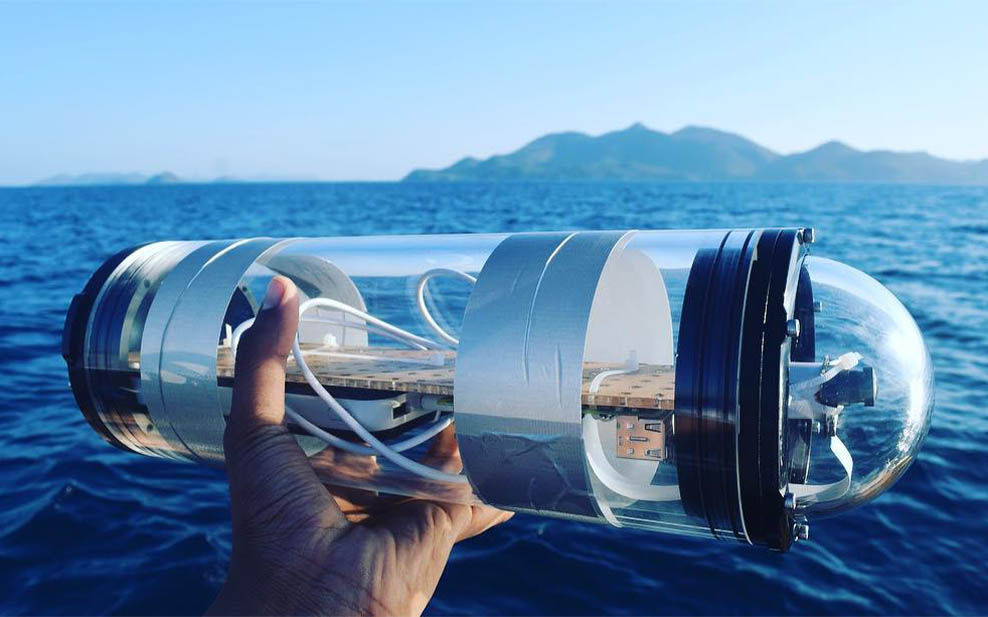

As on land, marine ecological research heavily involves the (ideally long term) use of remote field cameras for collecting data on wildlife and tracking environmental changes due to climate change. However, Sidhant and his team realised that the way most researchers were using cameras was incredibly inefficient, often relying on crudely constructed homemade equipment. “They were taking a sensor from somewhere, a [GoPro] camera from somewhere else and literally assembling [equipment] themselves. And they’re not engineers. The stuff they were putting together themselves was super unreliable” he recalls.

Additionally, the cost of maintaining so many cameras was extraordinarily expensive (each one cost upwards of US$ 2000 per year). They would also keep recording even when there was nothing to film, wasting both internal storage space and the time of researchers, who had to manually review around 72 hours of footage for just a few relevant sequences.

As a solution to these problems, Sidhant and his team invented Open Ocean Cam, a much less costly and more efficient alternative. Open Ocean Cam contains a camera and multiple data-collecting sensors all in one unit, removing the need for manual assembly. It has a 4-week-long battery life and can be easily controlled remotely through an accompanying phone app, helping to cut down on trips to retrieve it from the field and the associated fuel and manpower costs. With a 2 terabyte (2000 gigabyte) memory, it can collect much more footage than a GoPro and also uses AI to automatically sort photos and footage according to the subject being recorded, saving hours of time in sorting them manually. Finally, it is very durable and can be installed at depths of up to 400 metres.

Despite the youth of Open Ocean Cam –Sidhant’s first start-up–its product has already yielded impressive results. There are around 40-50 Open Ocean Cams deployed in the Philippines, Indonesia, Canada, the USA, South Africa, Mozambique, the UK and many other countries. The data their cameras have collected is also far superior to the GoPros that were being used previously, collecting on average 2-3 times more data. In addition, the remote control features have allowed them to film in hard-to-navigate areas.

While Sidhant relishes these initial successes, he is intent on continuing to develop the camera’s capabilities “Now that we’ve sold a few cameras, we now are trying to improve the product and make it [even] more reliable.”

Clearbot

Sidhant’s other innovative start-up is Clearbot, which produces small, semi-submersible robots of the same name to improve ocean plastic clean-up methods.

The inspiration for Clearbot came from a service learning trip to Bali, where every day the beaches are buried by up to 60 tonnes of plastic pollution. Despite valiant efforts by the locals to clean it up, their piecemeal methods –removing plastic by hand or with fishing nets– simply weren’t making a dent in the problem. Moreover, as Sidhant and his friends saw when they returned to Hong Kong, oftentimes clean-up crews use gasoline powered boats to clean up trash, creating further damage. “They’re causing pollution while they’re cleaning it up” says Sidhant. “We said ‘there has to be a better way”’. Thus, they decided to invent a device that could collect litter more efficiently.

The prototype Clearbot they assembled in Bali showed promising results in field trials –conducting automated clean-ups at twice the rate of conventional methods. So later, with research support from HKU and the funds raised from Saving Face and Open Ocean Cam, Sidhant founded his second start-up to scale up the impact of Clearbot. When his nascent company went on to win a start-up competition, that strengthened his resolve to move forward with growing it. “[That] became validation for us, that this can be a real business and we can really make this happen.”

Clearbot comes with a camera, sensors and a sophisticated data collection system, the latter of which analyses and classifies the collected litter according to type and recyclability. “Eventually, that gives us an idea into what this waste looks like and potentially, where it might be coming from” Sidhant explains. It can be remote controlled or operate on autopilot for 4 hours using sensors or GPS, making it totally emissions free. As it only costs HK$ 40,000 to build and incurs no fuel or manpower costs, it is also 15 times cheaper than conventional clean-up methods. Most crucially, it is easy to build and replicable, allowing for maximum impact.

“Imagine you have a group of three people trying to clean the water. There’s a very limited capacity to what they can actually do [by themselves]” says Sidhant. “Now imagine a fleet of Clearbots and the same people controlling 20 robots which are working on their own. Suddenly, that same group can really scale up what they’re doing. [They’re] not collecting ten bags a day, [they’re] collecting forty bags per day.”

A Technological Future

Some might question whether we should be placing so much stock in technology to solve our problems. Others might say that building and advancing technology to the extent that we have is what caused these existential crises in the first place.

But Sidhant doesn’t agree. His view is that technology is merely the enabler of the big changes that we’ve caused in the world, not the root cause. “[It] empowers humans to do what humans do, good or bad.” Rather, the real root cause is human imagination (or lack thereof). And that to him is cause for great optimism, because it means that with the right type of imagination, we could harness our technological power to make truly seismic changes for the better.

Why does he think this? Because we already have.

“If you look at the last Industrial Revolution, that technological change came with its own set of problems and over a period of time, we’ve fixed a lot of those major issues” he says reassuringly. “Now we’re actually moving towards a world that’s emission free. I very realistically think that in the next 20 years, we’re just going to see electric cars.”

It’s clear that Sidhant’s ambition is to be a driver of this new technological revolution. That is why he is working to build on the success of his current inventions to amplify their positive impact, particularly Clearbot. At the time of writing, five working models –previous ones were only prototypes– are active in the field: three in Hong Kong, one in India and one in Panama. By June 2022, Sidhant and his team plan to have built two new Clearbots for Hong Kong, with many, many more to follow in the future. “The goal for us is how do we get to 100 boats? How do we get to 1000 boats? How do we make this the new normal?” Achieving this goal will require serious money, which is why they are also looking to attract investor support for this project.

“Going forward, what we really want to do is make an impact and also be financially sustainable” states Sidhant. “If we’re able to consistently make a profit, that allows traditional investors financial systems to really support us […] and if we make an impact, then the bottom line is we’re changing the world.”

Cleaning up the planet isn’t the only thing Sidhant hopes to achieve with his inventions. In putting them to use, he also aims to help people from poor and marginalised coastal communities who depend on a healthy ocean and are the least able to cope with environmental degradation. To him, having the basic privileges necessary to do what he does places a responsibility on him to help those who don’t. Ultimately, it is that need to be the change he wants to see in the world that really drives him.

“I had a very privileged existence, I grew up in a very nice family, I went to a great university. Most people don’t have those opportunities. So for me, I need to make the most out of my life because I was lucky enough to have those things. So I really want to make a difference, I really want to change the world in the best way possible.”

Of course, becoming that sort of changemaker is no easy path, even for someone with Sidhant’s advantages. To many, the fear of failure or not knowing where to start makes it a daunting task even before they begin it. But in a world where the need for drastic societal change becomes clearer by the day, it is a path that more and more people are nonetheless aspiring to.

So to them, Sidhant’s advice is this: Know what you want, go for it, view failure as a learning experience –not an insurmountable barrier– and above all, always, always put passion into what you do. Do this, he argues, and eventually you will have an impact far greater than what you thought was possible.

“In my journey, even if I just started working on something I was passionate about on the side, that’s eventually how we’ve created something more meaningful.”

To learn more about Sidhant, check out his website: http://sdhntgupta.com/

For more details on Open Ocean Cam, check out the brochure here.

Finally, here are a few quickfire questions and answers to help you get to know Sidhant better. We asked him to say the first thing that came to mind when we said the following words. His responses are in italics.

ClearBot: Impact

Technology: Impact (again)

Open Ocean Camera: Marine conservation

Robots: I love ‘em

Hong Kong: Amazing city

India: Hometown

Plastic: Out of the water

Ocean: Beautiful

Corals: Bleaching (sad)

Purpose: Important

Hope: Important (again)

Future: Humanity

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Thomas Gomersall

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social media for daily news, competitions, and more.