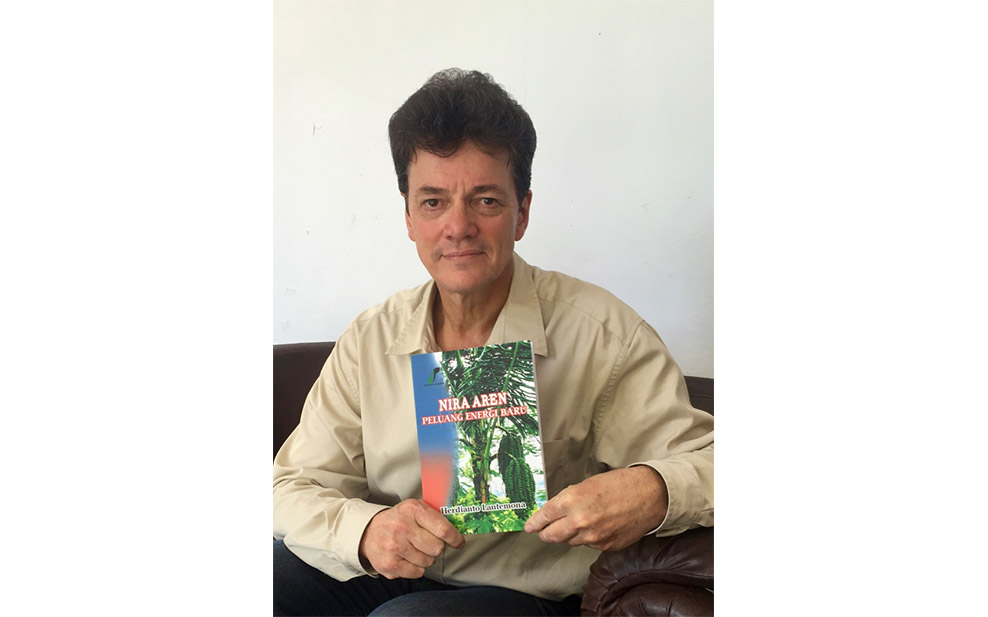

Willie Smits: The Innovator saving the Indonesian Rainforests

Prefer not to read? WELL, listen to this article by clicking on the player

Once upon a time in the early 2000s, Masarang Mountain in North Sulawesi, Indonesia, was a barren, useless area of steep land where once there had been lush rainforest. On most days, the pitiless sun would beat down endlessly on the ground. In the rainy season, the exposed soil easily washed away, quickly turning a trickle into a landslide that inundated villages at the base of its slopes.

For Dr. Willie Smits, this is an all too familiar scenario. Over his illustrious career saving Indonesia’s lush rainforests, he has been dismayed to see the continuous destruction of pristine ecosystems for palm oil and other industries. The sad result of business’s insatiable greed- tracts of land like this one, devoid of precious life.

But all hope is not lost. Fast forward to today and Masarang Mountain has come back to life. The rainforests have regrown and with roots binding the soil in place, landslides are a thing of the past. Once dry springs now bubble with fresh water again. Wildlife too has returned to call this land their domain, including critically endangered species like the crested black macaque.

The reason for these turnarounds? The dedication of Dr. Smits, whose work inventing new ways to restore forest have made all the difference. From employing new forestry management techniques, to re-involving the local community as stakeholders in the forests’ success, he has pioneered a new, more effective way for nature to reclaim its lost vibrancy.

Though not especially well-known in international circles, Willie is a leading figure of environmental protection in his adopted country of Indonesia. Since the 1980s, he has worked as a senior advisor for the minister of forestry, founded several environmental NGOs and helped to rescue thousands of animals (especially the endangered orangutan) from the wildlife trade.

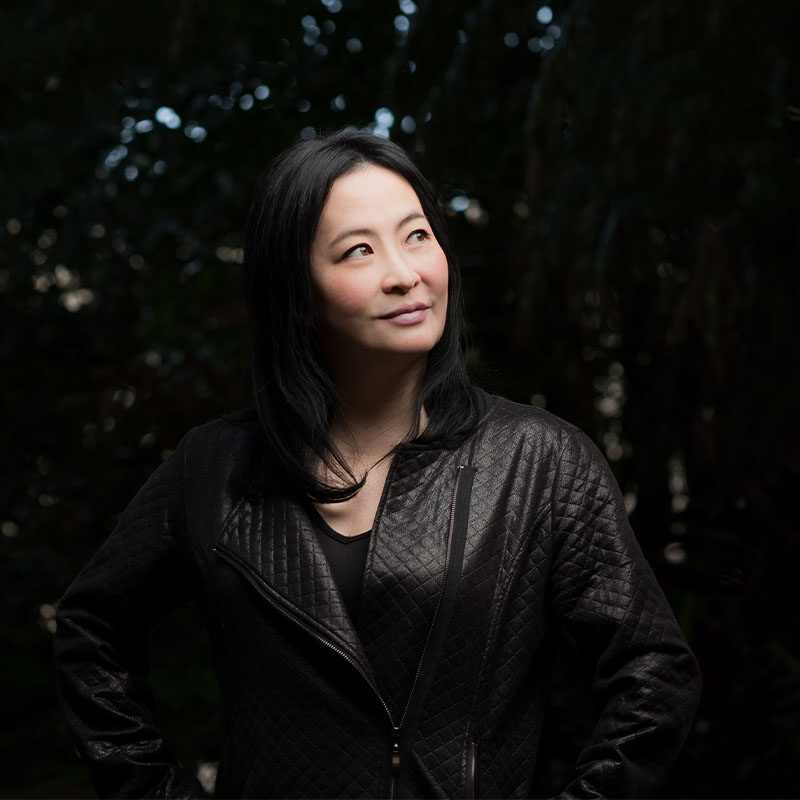

In this WELL, WHO? Feature, we share Willie’s incredible story, from his underprivileged childhood in the Netherlands, his early scientific breakthroughs, to his current work championing sustainable, equitable development and conservation. What is revealed is a man driven by compassion for humans and animals –particularly our closest evolutionary relatives– whose genius application of science and innovation promises to make the world a better place for us all.

A Dutch Start

Willie was born in a small village in the Netherlands, to a farm worker father and a dressmaker mother. His childhood was plagued by disadvantage, including a struggle with autism for the first five years of his life. More acute was his family’s destitute financial situation, which forced them to deal with problems that would be unimaginable to most Dutch families today.

“I would hear my brother and sister crying at night from hunger. [We] were living in a cupboard of two-by-two metres with five people on one bed” Willie recalls. “It wasn’t the easiest of upbringings.”

One advantage of growing up on a farm however was being surrounded by animals, which for Willie were a welcome relief from the harsh realities of life. “When I was two years old, I ran away from home. They found me after eight hours hugging the biggest, meanest guard dog in the neighbourhood” he reminisces. As he grew up, he continued to harness his love of animals, getting into birdwatching at the age of six, writing his first article on barn owl behaviour at twelve and even setting up his own rescue centre for injured owls and falcons.

When the time came to decide his career path, Willie initially wanted to study veterinary sciences at the University of Utrecht, the only place in the Netherlands that taught it back then. But upon arriving there for the pre-enrolment introduction, his dream was shattered by people who told him he had little prospect of employment as a vet. “It was all so negative that I decided that I never wanted to go back to the city of Utrecht.”

Disheartened and with no path forward to his desired career, Willie was left unsure of what to do with his life. But then, a friend offered him a room in Wageningen, home to one of the Netherlands’ (and the world’s) best environmental universities. Finding a closer fit to his interests and a more supportive community, in 1975, he enrolled there on a seven-year tropical forestry course.

For the first three years of university, Willie was more into partying than studying, unable to muster the same passion for forestry as he had for animals. His lack of effort caught the eye of the school’s Dean, who one day told him to get serious and pass his upcoming exams or leave the course.

Fortunately, he soon got the motivation to do that when he attended a lecture by a professor of tropical forestry. “I went into that room and sat in the back, contemplating my life. Then he started talking about trees and interactions and I was amazed and said to myself ‘you’ve been wasting your time’” he recalls.

Inspired by the professor’s lectures on trees and the interconnected life of rainforest species, Willie finally felt the dots connecting – this was, after all, something he could excel in, if only he applied himself. In the lead-up to exams, he spent every spare moment cramming several years’ worth of study into six weeks, performing well enough to impress the Dean into allowing him to stay on the course.

From then on, Willie’s mission in life was set – to apply himself to the study and protection of tropical forests and all the amazing species that called them home.

The Seed of a Career

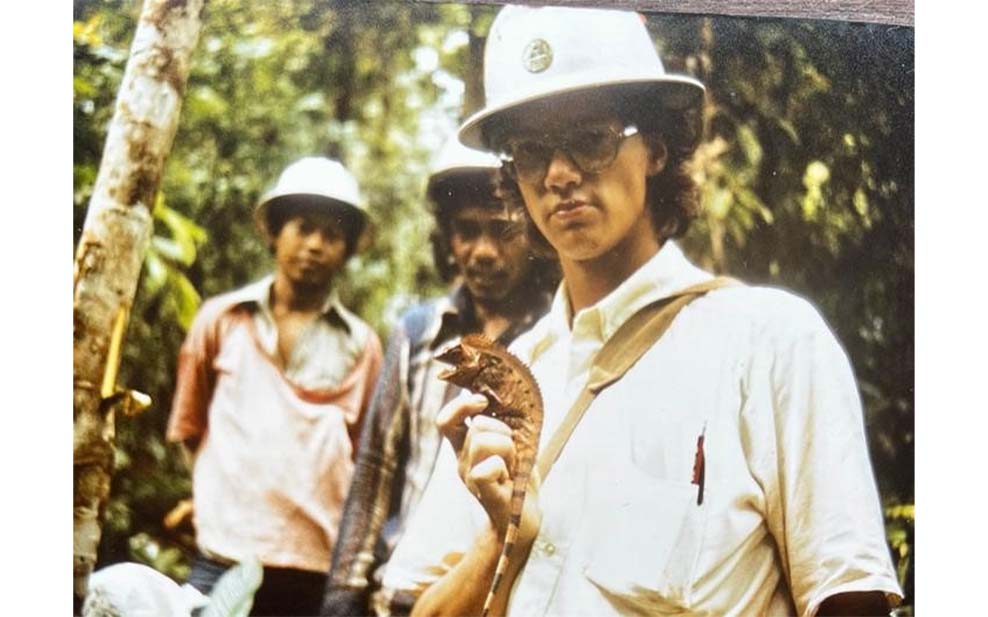

Part of Willie’s university course included doing six months of practical fieldwork abroad. With help from a lecturer, Willie ended up doing his fieldwork on a timber concession in the province of East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo.

“That’s where I really fell in love with the beauty of the forest” he reminisces fondly. In fact, between 1980 and 1985, he would travel back-and-forth between Indonesia and the Netherlands.

During his fieldwork, Willie became interested in growing rainforest trees in captivity – propagating forest with saplings could be key to spurring new growth in dead zones. While unsuccessful in the past, he reckoned it could be done.

However, when he first attempted to grow seeds collected from Indonesia with the University of Wageningen’s Department of Forest Ecology, he was likewise met with failure. Undeterred, he continued his research, eventually coming across an 80-year-old publication mentioning how microscopic, symbiotic fungi on the roots of these tree species could aid their growth. However, multiple attempts to add various fungal species to the soil around his trees also yielded little success.

Finally, Willie realised that the specific fungus his trees needed would have to come from their home turf. Sure enough, after a colleague brought back soil (and its attendant fungus) from around the tree where he’d collected his seeds, he found that his saplings shot up in size.

“That was how I came upon this idea of using fungi to propagate plants” he says.

Around this time, a professor from an Indonesian university was visiting Wageningen and was gobsmacked by Willie’s experiments. “He said ‘What? You solved that? We’ve been trying to do that for 100 years!’” A week after he left, Willie received a visit from an advisor to the Indonesian minister of forestry, who questioned him about his work. Two weeks after that, he was invited by the minister himself to apply his discoveries to real-world forestry in East Kalimantan with the backing of the Wageningen Agricultural University.

Thrilled at the chance to return permanently to Indonesia and apply his work to a real-life project, Willie packed up his things and moved to the country that had captured his heart.

Growing Strong

When Willie returned to Indonesia permanently in 1985, he set out to find a suitable site to conduct his research at. He decided that for his work to have maximum conservation benefits, it needed to be somewhere where it could be easily seen.

“I thought if I wanted to achieve anything at all, people should learn about it” he says. “If you’re working in a remote location in the forest, people might believe what you’re writing about, but they can’t see it.”

He found what he was looking for at the Wanariset Tropical Forest Research Station. Though it was a derelict wreck at the time, it was on the main road between two of East Kalimantan’s major cities –Balikpapan (where the international airport was) and the capital, Samarinda. Thus, it was in an ideal location for people –especially officials travelling between the airport and the capital– to visit. So, he fixed up the station and used it to grow trees using the methods he had perfected, to results so impressive that his work soon started getting plenty of attention.

“People started talking. I started getting invited to Jakarta to give lectures on these methodologies” he says.

Among the interested parties was Tropenbos, a Dutch non-profit organisation for sustainable tropical forest management. To them, Wanariset was a perfect location for their Kalimantan programme and Willie’s work was very much in line with what they wanted to do. Naturally, they saw him as the perfect team leader to spearhead the initiative.

In this role, Willie set up a forestry training unit at Wanariset. Here, he worked with and supervised many researchers and trained 1,100 local foresters in tree identification and propagation techniques. The growing impact of his work attracted the attention of universities around the world, including Harvard, who invited him to speak about it.

“We produced many, many publications in that time. A lot of MSC students” he remarks proudly. “I published five manuals for the various propagation techniques of primary rainforest tree species”

As his profile continued to grow, so too did his opportunities. In 1992, he was offered a job as a senior personal advisor to the minister of forestry. This allowed him influence over more than just Wanariset, enabling him to write proposals for law changes to the Indonesian parliament. He also accompanied the minister on international trips, including one as a parliamentary advisor to a conference in Washington DC organised by Al Gore.

But despite his career’s heavy focus on forestry, Willie never lost his passion for animals. Four years after permanently moving to Indonesia, a chance encounter with one would finally allow him to work with them.

The Orangutan Man

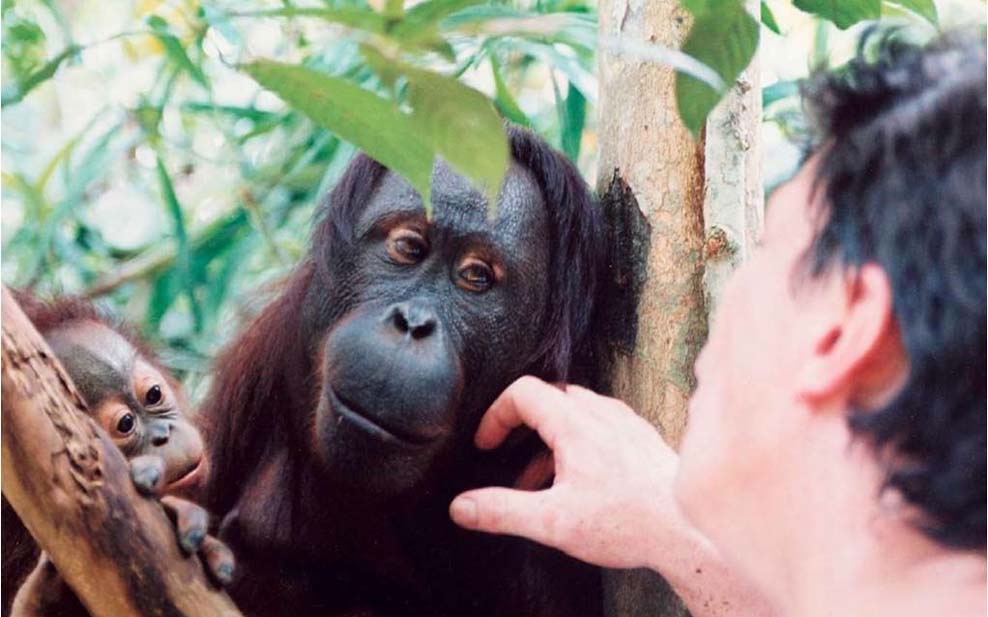

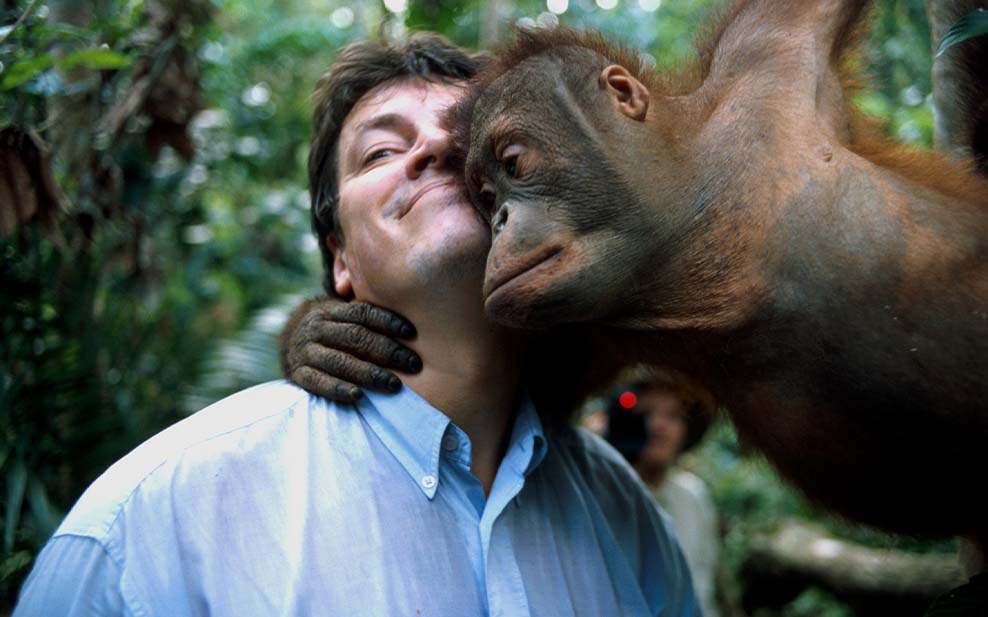

In 1989, Willie was visiting a vegetable market in Balikpapan when someone tried to sell him a very sad, very sick baby orangutan. Shocked and horrified by her condition, he returned to the market that night after closing time, finding her abandoned on the garbage dump to die.

Willie named the baby Uce (pronounced ‘oochay’) –after the laboured breathing sound she was making– and brought her home with him. Two weeks later, as word of his rescue of Uce spread, he received another orphaned orangutan (a male this time) from the wife of a forestry official, which he named Dodoy.

Despite the difficulties of juggling taking care of them with his job and a young family, he was able to nurse both orangutans back to health. Through this, he became more interested in orangutan conservation. However, he was frustrated to find that most NGOs that were supposedly focused on helping them simply weren’t doing enough. They seemed more about offering photo-ops than actually protecting them.

Deciding to apply his new hands-on experience in orangutan welfare, Willie decided to found his own NGO, dedicated to helping the growing number of displaced and threatened orangutans in the jungles he was fighting to protect.

“The two of them became the beginning of my various orangutan projects” he says of Uce and Dodoy.

However, few of Willie’s colleagues were as keen to get involved with this as him. Luckily, he was able to find an unusual, but highly enthusiastic, group that he could turn to for reliable funding.

“For the first three and a half years, it was only the schoolchildren in Balikpapan that donated their pocket money and did baking and spelling contests to raise money” he recalls. “[They] each gave tiny amounts –10 cents per month– but it kept me going.” Some of these children even became informants for Willie and his organisation –then called the Balikpapan Orangutan Society–, tipping them off about orangutans that needed rescuing.

Willie’s passion project has grown year over year, achieving astonishing results. Since its founding in 1991, the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (as it was rechristened in 2003) has become the world’s largest NGO for primate conservation. It has gone from just 2 orangutans to rescuing 1500 from circuses, the pet trade and from medical research. From just Willie and his partner, the staff has grown to 450 people. It has also expanded its work to protecting orangutan habitats, including 300,000 hectares of peat swamp forest and 88,000 hectares of dryland forest. Furthermore, it has retrained former poachers in more sustainable means of income, like farming fruit and rattan.

As for Willie’s first two orangutans, they too have come a long way from being left for dead. On May 23rd, 2022, Uce will celebrate her 30th year as a fully wild animal. And the father of her second baby born in the wild? None other than Dodoy himself!

Masarang

Throughout his work with Tropenbos on reforestation, the minister of forestry and his orangutan foundation, Willie had another project on the go. One that has made waves in transforming conservation in Indonesia.

In 1980, he learned that a marriage custom in North Sulawesi was to pay a wife’s dowry in the form of six Arenga sugar palms. Given that each tree cost about as much as a chicken, at first it seemed to him like a pittance. “Why would just six palms be a dowry? It didn’t make sense to me” he remarks.

But upon doing further research, he realised that the tree was actually a highly productive, versatile food source. Monetised to their full potential, the profits from six Arenga palms were enough to support a young family. And the food security benefits were even greater.

“You [can eat] the palm heart, you have sugar [from the sap], you have starch in the middle of the stem. You have larvae in the dead stems. You have all these food sources” Willie reports. “From one hectare of sugar palm forest, a village of 500 people would be able to survive, calorie wise, for 6 months.”

Willie decided to trial this more beneficial type of palm in his research and discovered that it could not only grow on deforested land and steep slopes, but would only grow well if surrounded by a diverse mix of plant species. Thus, it was potentially a powerful tool to restore degraded land to biodiverse ecosystems.

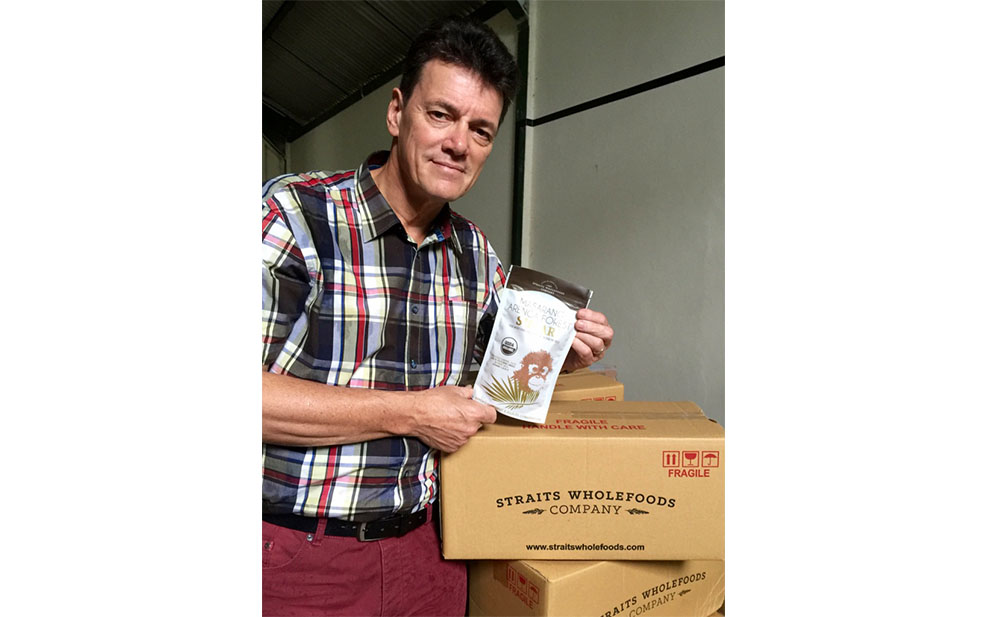

However, in most cases, the tree was being underutilised both as a reforestation tool and a means of income. Seeing another opportunity to make a big impact –one that meshed well with his ongoing conservation initiatives– in 2001, Willie founded the Masarang Foundation, named after a mountain near the city of Tomohon in North Sulawesi. His vision was to create a sustainable market for sugar derived from the Arenga palm’s sap that would maximise the profits for local people, while also reforesting decimated land.

But, as with his previous ventures, starting out wasn’t so easy. Firstly, tapping the Arenga palm for sap was more complicated than first anticipated, requiring years of training and a vast array of skills. “There are about 60 components to tapping the stem in an optimal way and how to prepare and treat [the sap].” The remote location of the palms and the sap’s rapid rate of decomposition after harvesting also created logistical difficulties in processing it into sugar. Further complicating the process was finding a sustainable source of fuel other than firewood from the forest to heat the sap into sugar.

Luckily, Willie found a geothermal energy plant near Tomohon and arranged with them to use their waste steam to heat the sap. He also built a system of pipelines to bring the sap from collecting points in the forest to vehicles for quick transport to the plant, making the logistics more time efficient.

The most crucial part of the operation was ensuring that sap harvesters and their families –not middlemen or exporters– got the lion’s share of the benefits. To do this, Masarang worked to help the harvesters obtain organic certification to get a better price for their sugar. They also raised money to get each harvester good quality palm seeds, insurance and a pension. In exchange for Masarang’s benefits, they were contractually obliged to protect their individual plots of forest from poachers and illegal loggers.

Now, 21 years later, the benefits speak for themselves. From reforesting a few hundred hectares of Masarang Mountain itself, the organisation and its trainees have to-date planted around 35 million trees, restoring ecosystems in Sulawesi and Kalimantan that once seemed beyond hope. “We have monkeys back, we have birds back, those forests have come alive again.” In addition, Willie has also set up the Tasikoki Wildlife Rescue Centre in Sulawesi to rehabilitate animals rescued from the wildlife and bushmeat trades –financed in part with excess sugar profits– for the which the restored forests make ideal release sites.

More importantly, the prospects of the local people have also improved greatly. Communities with Masarang contracts now have some of the nicest housing and have seen their income increase tenfold from 30,000 to an average of 320,000 rupiah per day. Thanks to the improved hydrology of mixed sugar palm forests, there is now more water for their rice fields. Masarang has also planted fruit and timber trees alongside Arenga palms to diversify their income. For Willie, the human prosperity created by his projects is what truly underpins successful conservation work, as his own impoverished childhood taught him.

“If you’re hungry, you don’t think about conservation. If you’re hungry, you don’t think about the future of a forest or orangutans” he points out. “That’s why I’ve come up with this philosophy that the only way we can have a future for our planet is if we make it work for everyone.”

A Way Forward

For all of its perks, being a conservationist can be deeply sobering too. Watching the habitats and species you love vanish while society at large remains indifferent can wear heavily on one’s psyche. This is particularly true in Indonesia, which every day loses vast tracts of rainforest to feed a seemingly unquenchable demand for palm oil. Conservation is also notoriously underfunded, making fighting back against the powerful business interests destroying our planet even harder.

“I’m pissed off!” Willie seethes. “I’m extremely angry at what’s happening to our world because of the stupidity of a lot of people who just see the short-term profits and do not understand the big danger that we are heading straight into!”

Adding to an already challenging environment is, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic, which has all but ground Masarang to a halt. Tasikoki Wildlife Rescue Centre, for instance, can now barely afford to feed the animals in its care and recently had to turn away 200 new ones. Due to COVID regulations, the volunteers and paying guests that formed so much of the centre’s workforce and financial backbone have dried up, while many paid staff have had to be laid off. School visits in cities like Hong Kong to spread awareness have also been disrupted.

“It has been absolutely devastating. That [we’re] still around is a miracle” Willie bemoans. “We’re only barely hanging on.”

But as long as they are hanging on, he and his colleagues will keep soldiering on. Dealing with adversity has, after all, been Willie’s skill since childhood. He draws strength from both his righteous anger and his accomplishments. Several of his former students from Wanariset, for example, now hold important positions in Indonesian politics and are working to change the system from within.

In the present meanwhile, Willie is keeping himself occupied writing poetry, music and even a (semi-fictional) book about orangutans called ‘Mawas Days’. He is also developing a new software to estimate the agroforestry potential of an area and provide a roadmap for obtaining maximum social and environmental benefits from it, in Indonesia and beyond.

“I’m trying to put what I have learned in the last 43 years in the field into a system that others can use” he explains. “That is my hobby, solving puzzles and connecting dots.”

In Willie’s view, if any good is going to come from this difficult time and the ones ahead, it will be a greater realisation amongst people that they need to protect the environment and push for a sustainable future to survive. This in turn should create more career opportunities for those wanting to work in conservation. So to them, his advice is this:

“You can make a difference. It’s not going to be easy, but you have to persist. […] There are going to be opportunities. So go for it!”

If we are going to survive and flourish, it is imperative that we channel the spirit, energy and scientific smarts of people like Willie Smits. Our lives, and the lives of the wild animals who share our fragile planet, depend on it.

Before you go:

Masarang urgently needs operational funds for electricity, internet, fuel, animal feed and salaries. If you are able to donate, please consider checking out their donation page: https://masarang.eu/donate/

Finally, here are a few quickfire questions and answers to help you get to know Willie better. We asked him to say the first thing that came to mind when we said the following words. His responses are in italics.

Orangutan: Sentient beings

Indonesia: Beautiful

Netherlands: Everything taken care of already

Rainforest: The most beautiful systems in the world

Fungus: Exceptional importance

Masarang: The way forward

Arenga Palm: Tree of life

Conservation: The only way

Research: Important

Purpose: Very important

Hope: It springs eternal

Future: Uncertain

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Thomas Gomersall

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social media for daily news, competitions, and more.