According to one study, Hong Kong’s seas are home to a whopping 5,943 species. But only one can be safely described as a beloved animal in the public eye: the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, known locally as the pink dolphin.

Although this species is fairly widespread across Southeast Asia, the largest of the few, fragmented populations in Southern China can be found in the Pearl River estuary. In Hong Kong, pink dolphins occur almost exclusively in near-shore habitats off the west and southwest coasts of Lantau Island, where (for now at least) they can be spotted in small groups averaging three individuals. Meanwhile, their playful demeanour and the bubble gum pink skin of the adults (calves are born grey) have also made them an icon of local marine conservation.

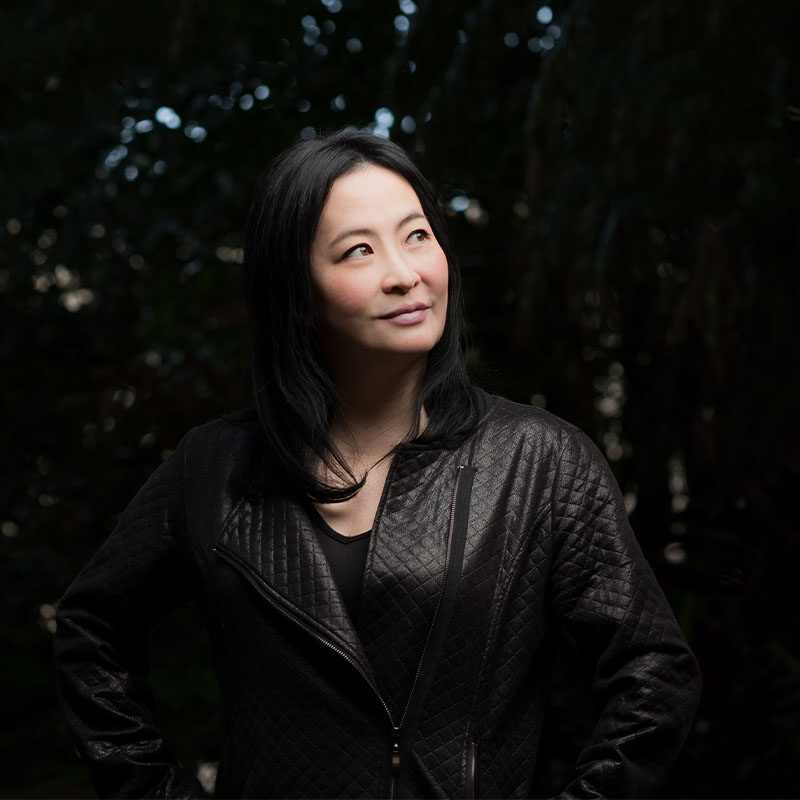

However, this might never have been the case were it not for the efforts of Dr. Lindsay Porter.

As recently as the 1990s, very little was known about the pink dolphins of Hong Kong. At that time, Lindsay was still a fresh-faced marine sciences graduate working in her native Scotland. But through contacts made during a summer in Hong Kong as an undergraduate, she found herself being invited back to conduct the first comprehensive study of the dolphins. In the process, she not only gave our scientific understanding of this species a much-needed boost, but also helped to transform it into a darling of the Hong Kong public; a sentiment that has persisted to this day.

Now, nearly 30 years later, she is one of the world’s leading experts on pink dolphins and has used the knowledge from a lifetime of experience to spearhead the development of marine mammal research elsewhere in Asia. However, she still continues to study the Hong Kong dolphins: a vital, sometimes sobering task given their rapid, ongoing demise in an ever more polluted and developed seascape.

In this WELL, WHO? Feature, we dive into Lindsay’s story to inspire those interested in saving the pink dolphin (before it’s too late). Hers is proof that by making the right contacts, accepting opportunities when they come and being willing to do what hasn’t been done before, you too can help make real strides in safeguarding the future of our oceans.

Water Baby

Lindsay was born in Glasgow but moved very shortly afterwards with her family to South Africa, where she spent most of her childhood (and picked up the local accent). Growing up in rural areas of the country and with school days ending at noon, she had plenty of time to spend playing outside. In fact, it was during family holidays in Durban that she saw her first dolphin and gained her sense of awe and respect for the ocean’s large animals, albeit in a way that might have had the opposite effect for many people.

“I remember swimming in the sea and being told to come out of the water whenever sharks were sighted in the area” she reminisces fondly. “I don’t remember it being particularly scary at the time. I just recall that was part of being in the ocean; that you had to be very conscious of the other animals living there.”

Eventually, the Porter family moved back to Scotland –living once again in the countryside– in time for Lindsay to begin high school. There, she quickly regained her Scottish accent and later went on to study forensic sciences at the University of Glasgow. But for such an outdoorsy person, the charms of being stuck inside a low-lit laboratory all day were quick to wear thin.

What she enjoyed much more was the subsidiary course in marine sciences that she was taking at the same time, which prompted her to switch full-time to Aquatic Biosciences. As part of this course, she got to spend a lot of time outside doing fieldwork, which was what cemented her passion for marine science.

During Lindsay’s university years, she had an uncle living in Hong Kong who invited her to visit him for a summer, even arranging for her to do her undergraduate project at the University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s then-newly opened Swire Institute of Marine Sciences (SWIMS). Thus, it was on the shores of southern Hong Kong Island in 1991 that Lindsay first came to know the place that would later become her home.

“That’s when my love of Hong Kong began; when I came here as an undergraduate and I spent the summer on the rocky shores of Cape d’Aguilar studying thermal stress in barnacles and mussels” she recalls.

From UK to HK

Needless to say, studying marine mammals is much more challenging than studying shoreline shellfish, as they tend to live in remote offshore areas and spend most of their time underwater, out of sight of humans. Overcoming these challenges requires a lot of innovation, deciding the best techniques and technologies to use and sometimes having to invent new ones.

But despite the discouragement of her undergraduate supervisor, Lindsay was not put off by these difficulties. In fact, the more she talked to those who worked in marine mammal research, the more determined she became to work in it too. “As I met more marine mammal biologists and saw what was really possible, I decided that was the career for me and thereafter strove to become part of that field”.

Lindsay’s first taste of how challenging this career could be came with her first job. Stationed in the Black Isle in northeast Scotland, she worked with a programme monitoring the recovery of Britain’s seal populations from a recent disease epidemic. As part of this work, she and her colleagues had to catch seals, take blood samples from them and analyse those samples for viruses. A simple job in theory, but not when dealing with a large, powerful, surprisingly aggressive animal in practice.

“When you’re trying to catch an animal that [weighs] 250 kilos in a gentle and caring way, it can present all sorts of challenges” says Lindsay.

Nevertheless, she thrived in her work and regularly kept friends, family and colleagues updated about it. This included the people she had met at SWIMS and keeping them in the loop would be instrumental in shaping her later career.

In the 1990s, the scientific community in Hong Kong was becoming increasingly interested in the local pink dolphins. However, as no serious research had been done on them before, almost nothing was known about them and nobody in Hong Kong was qualified to study them. But, knowing that Lindsay was both familiar with the local marine environment and had relevant experience, her contacts from SWIMS invited her to come and do a PhD on the pink dolphins. Looking back, Lindsay credits her seal-wrangling years not only with getting this offer, but also with giving her the skills to carry out the work.

“I think I would have been utterly unable to conduct a PhD if I hadn’t spent two years in the field learning how to study wild animals as I did with the seal population” she remarks. “I’m also a little bit independent, which helps enormously.”

Making a Splash in Hong Kong

Lindsay arrived in Hong Kong in 1993 to begin her PhD (coincidentally, while fellow marine conservationist, Andy Cornish, was doing his) at HKU. From the beginning, she was well supported by her supervisor, the late Professor Brian Morton, who encouraged her to follow her passions when doing her research.

“He basically told me to go forth and choose what I wanted to study, but to come back in three years with a good PhD” she recalls.

With so little information about Hong Kong’s pink dolphins available at the time, Lindsay chose to focus on one of the basics of species ecology: the distribution of the population. To do this, she first identified individual dolphins by photographing their dorsal fins and then followed them around on a day-to-day basis, recording where they went and what they did. “I feel incredibly privileged, because I was one of the first people in Hong Kong that began to take images of dolphins within [this] habitat and they are striking and remarkable to look at” she says of her PhD and study species.

These photos weren’t just good for her research. When the first ones were circulated in the media, they also gave the Hong Kong public their first real exposure to the dolphins. With their pretty pink skin, they were an instant hit and the resulting media frenzy even led to them becoming the emblem for the 1997 reunification with China. And while public interest is not quite as high now as it was then, it has very much not gone away.

After three years of fieldwork, Lindsay had discovered that the dolphins along the west coast of Lantau were split into two distinct populations: a northern one and a southern one. But while her PhD created a previously non-existent baseline of information, it was nowhere near enough on its own to give a complete picture of the dolphins’ lives or ecology. “These dolphins live for 40 to 50 years. So if we’re only looking at 3 years of their lives, we’re not really getting a proper baseline of information” she says of the limitations of her PhD. “With all conservation issues, particularly for long-lived animals, the solutions and the studies [have to be] long term.”

That’s why in the 25 years since gaining her doctorate, she has continued to regularly document both the dolphins and Hong Kong’s other resident marine mammal, the finless porpoise. In doing so, she has helped to build a much more comprehensive understanding of their population, distribution and resource use, as well as how the ever-pervasive threats of pollution, overfishing and coastal development have affected these.

“Since [my PhD], there have been many, many changes around Lantau Island and I’ve seen the social structure of the population change several times to accommodate the changing seascape that has been brought about by development” she says. For instance, a feeding ground at the Brothers Islands to the east of Lantau has been all but abandoned, possibly due to an increase in ferry traffic.

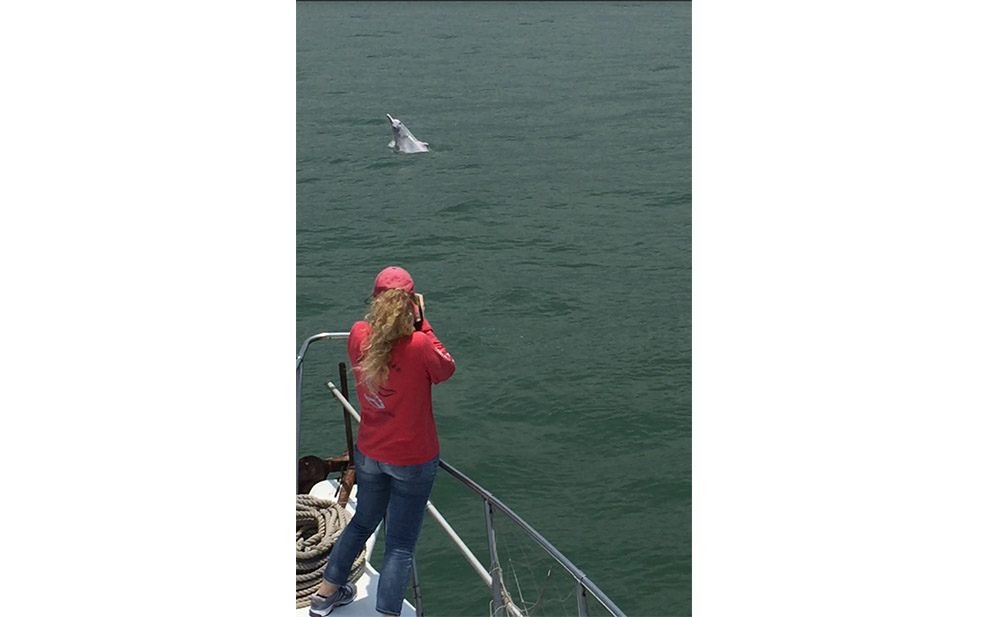

More recently, Lindsay has been turning to acoustic research, using underwater hydrophones to record and analyse the sounds made by dolphins and porpoises. As different sounds correspond to different behaviours, this allows for a more complete understanding of their lives beyond what they display at the surface. “We now have a very good idea of what [they] do daily and seasonally in Hong Kong, but also what their nighttime activities are” she comments. “For finless porpoise, they spend most of their time [at night] feeding. […] For dolphins, we think that more socialising occurs at night, but perhaps some additional feeding between midnight and 4 o’clock in the morning.” This method potentially also allows her to study the movements and behaviours of migratory cetaceans (dolphins and whales) that pass through Hong Kong, to determine the importance of local waters for these species.

Overseas Work

Lindsay’s influence on conservation isn’t limited to Hong Kong, because neither are the threats facing marine mammals here. Across the world, every species of near-shore cetacean is in decline due to human activities. Yet as exemplified by the lack of research into Hong Kong’s dolphins prior to the 1990s, marine mammal science has traditionally been very neglected in Asia, despite its vital role in conservation.

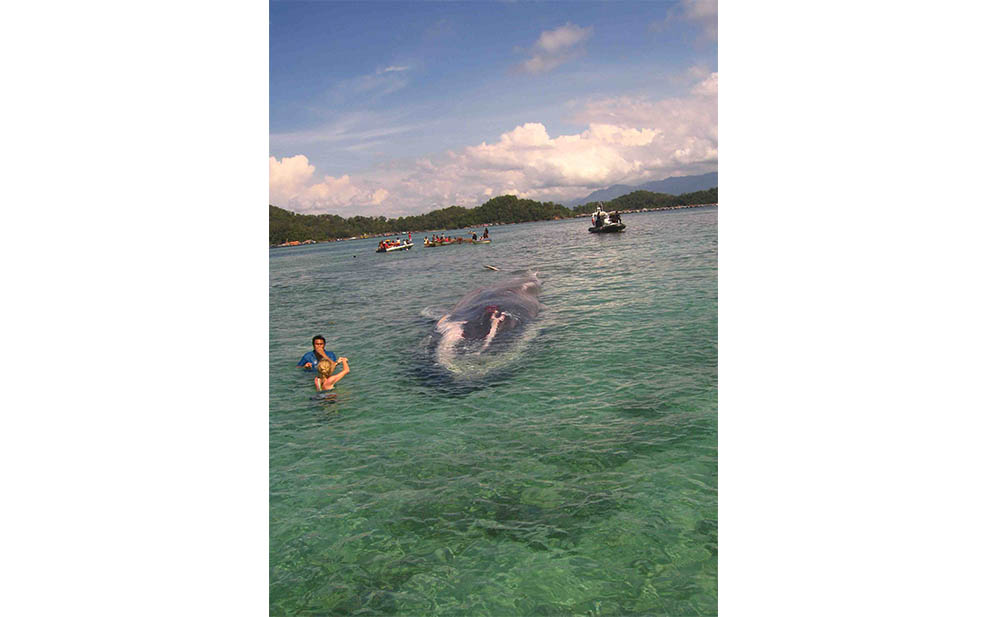

To help address this, Lindsay has expanded her work to other regions to try and understand the ecology and threats facing local cetaceans. One example of this is a project studying the distribution and habitat usage of pink dolphins and another species, the Irrawaddy dolphin, in Sabah in Malaysian Borneo, once again using dorsal fins to identify and track individuals. She also has a project in Sri Lanka studying blue whales, although this one is much less glamorous than it first sounds, as it involves sifting through their faeces in search of microplastics.

“I just want to assure [people] that being a marine mammal biologist isn’t all boats and glamour and taking photographs of gorgeous creatures” she quips. “You do [also] have to shift through the murkier aspects of their ecology”.

But as far as she’s concerned, her most meaningful achievement on these projects isn’t what she herself does. It’s getting the local people actively involved in them, be they scientists or even just ordinary citizens. “I’d like to think I’ve benefitted conservation a little in that way, because I’ve encouraged people to work within their countries on the marine mammal species that they have there.” In Sri Lanka, she works with two local universities and in Borneo, she and a local NGO have worked closely with villagers living on the Kinabatangan River, training them to spot and collect data on dolphins. “We try to bring the local community –the fishermen that occur in the dolphin’s habitat– and a local group who wish to conserve the forest and the river and the integrity of that habitat together.” To her, fostering this sort of co-operation between different groups on a local scale is key to strengthening marine mammal research in Asia.

Navigating Rough Seas

Sadly, despite the efforts of Lindsay and others, things for the pink dolphins of Hong Kong have largely gotten worse, not better, since the 1990s.

The danger of a species being specialised for a certain habitat –as the pink dolphins are for estuaries– is that it makes it very vulnerable to changes in that habitat and limits its ability to adapt or move elsewhere. And in the last few decades, the Pearl River estuary has changed drastically, much to the detriment of its dolphins.

Coastal development like land reclamation –most infamously for runways at Hong Kong International Airport– has degraded and reduced the areas of shallow water habitat that dolphins and their prey rely on. What little habitat that does remain is crisscrossed by shipping routes, leading to often fatal boat collisions with dolphins. Meanwhile, illegal fishing has devastated fish stocks and the fish that are left are loaded with industrial and agricultural toxins washed down from upriver. Finally, both development and boat traffic create deafening levels of underwater noise, which is an enormous hindrance for animals that rely heavily on sound to feed, socialise and navigate.

These ongoing man-made threats have taken a heavy toll on the Pearl River estuary’s pink dolphin population, which is now dangerously low. Scientists warn that unless drastic conservation action is taken very soon, the local extinction of this species is all but inevitable. Unfortunately for those concerned for their future, kickstarting said action is far from a straightforward process.

“The issue is that the problems that the dolphins face are not just one or two problems that can be easily fixed, but a whole myriad of issues that are complicated and cannot be easily teased apart from each other” Lindsay laments.

The overarching issue is that Hong Kong has only a small area of territorial waters and a lot of stakeholders with conflicting goals for using it, from fishermen to shipping companies to conservationists. Finding a balance that addresses the needs of wildlife without compromising the livelihoods of local people or the bottom line of corporations is therefore extremely difficult. “The obstacle is balancing all of those different activities and trying to keep everyone happy. And we all know you can’t keep everyone happy all of the time.”

Many have blamed the Hong Kong government for not doing enough to protect the dolphins. But Lindsay doesn’t take quite as condemnatory a view, citing the need to work with politicians to make conservation gains. She also points out what the government has done to alleviate things; namely establishing protected marine parks and banning commercial trawling in local waters.

However, the effectiveness of these measures is limited, as many important dolphin habitats are not protected within marine parks, which also still allow fishing with a permit (although this is due to be phased out soon). Furthermore, other threats like pollution –both chemical and noise– and boat collisions are still not being addressed, despite ongoing calls from NGOs like WWF.

For Lindsay, making Hong Kong’s marine space more friendly for dolphins is her next big goal, and she has seen for herself what could be if such a goal were achieved.

Safe Harbour?

For a period in 2020, marine traffic in Hong Kong all but completely ceased due to COVID-related border closures. Almost immediately, Lindsay witnessed a profound change in the pink dolphins’ behaviour. With no boats to run them over, they could expand into areas that were once too risky for them and enjoy a much quieter underwater world. Thanks to this much needed (albeit temporary) reprieve, the first year of the pandemic saw an almost unprecedented boost in the dolphin population, with 8 successful calf births. “We hadn’t seen that many new baby dolphins in at least 7 or 8 years in Hong Kong” Lindsay comments. For her, this is living proof of how quickly the dolphins could potentially bounce back if the threats facing them were adequately dealt with, starting with re-routing marine traffic routes to bypass dolphin habitats or by using them less.

“I know that that’s extremely challenging in a port such as Hong Kong, where we rely heavily on cargo ships and passenger vessels. However, if we’re serious about saving the dolphins, we need to think about what is achievable” she says. “Instead of having the ferries go from Mainland China and Macau, perhaps we can make more use of the Hong Kong-Zuhai-Macau bridge.”

Making any conservation action happen is, of course, a constant uphill battle and when the trajectory for the pink dolphins is as grim as it is, it’s easy to despair for their prospects. And yet, even while they continue to slip towards oblivion, Lindsay still finds hope and the drive to carry on. Some of this comes from her inherent curiosity about marine mammals –“Every time I see [them], I still learn something new.”–, some from their continued persistence against the odds, and some from keeping her mind occupied in her spare time through paddling and, whenever possible, horse riding.

But more recently, what has given her fresh hope is the ever-growing public awareness of how intrinsic the health of our planet is to the wellbeing of our own species as well as many others. “[The pandemic] has brought home to a lot of people that you cannot disconnect nature from the human population. We are part of this planet and the ocean is what drives the health of this planet. So to take care of the ocean and the animals that live in the ocean is something that helps us take care of ourselves.” The protection of marine mammals is important to this goal because, as top predators, they require healthy ecosystems to meet their needs and those of the species they prey on. So, as Lindsay notes, “if we can keep the environment healthy enough to sustain those populations, then for sure we’re making progress in keeping the ocean healthy enough to sustain us as humans.”

As for herself, she hopes to continue sharing and seeding her passion to protect the ocean and its wildlife amongst others. In particular, she hopes to continue helping to advance Asian marine mammal science. “There are not enough marine mammal researchers in Asia” she says. “If there’s one thing that I would love to be behind, it’s this passion and desire to preserve the mammals that live in our seas.”

And to those who she inspires or who already share her desire to conserve wildlife as a career, her advice is this: Don’t expect to get rich, but do expect a career rich in interesting people –from fishermen to politicians to fellow conservationists– and varied experiences.

“It’s a tough job. […] But it is so incredibly rewarding. What other job is there where your workplace is the ocean? Where you can be outdoors learning and being part of one of the great systems that drives our planet?”

Before you go:

To learn more about what needs to be done to safeguard pink dolphins, check out this Emergency Action Plan by WWF-Hong Kong: cwdleaflet_eng (d3q9070b7kewus.cloudfront.net)

Finally, here are a few quickfire questions and answers to help you get to know Lindsay better. We asked her to say the first thing that came to mind when we said the following words. Her responses are in italics.

Pink Dolphin: Hope

Hong Kong: Change

Scotland: Love

Ocean: Dolphins

Blue Whale: Immense

South Africa: Childhood

Paddling: Peace

Horses: Challenging

Conservation: Also challenging, but worthwhile

Seals: Smelly

Research: Fun

Purpose: To preserve

Hope: My Son (Connor)

Future: Also my son

Written exclusively for WELL, Magazine Asia by Thomas Gomersall

Thank you for reading this article from WELL, Magazine Asia. #LifeUnfiltered.

Connect with us on social media for daily news, competitions, and more.